Why We Should Split Up Our Four Biggest States. And Why We Can’t.

Americans would be better off requiring big states to divide.

Why not 57 States?

Federalism has time-tested benefits, which is why nearly every modern country uses it to distribute power between national and local governments. These benefits include:

Local autonomy. States and their counties and cities can more easily meet the unique needs of their populations.

Experimentation and innovation. States try different approaches and serve as “laboratories of democracy”.

Diffusion of power. By dividing authority, federalism helps prevent a national government from becoming too powerful.

Participation. Citizens can affect the policies of their state and local governments much more easily than they can the national government.

Balancing unity and diversity. Federalism allows a country to maintain national unity while accommodating the cultural, economic, and social diversity of its regions.

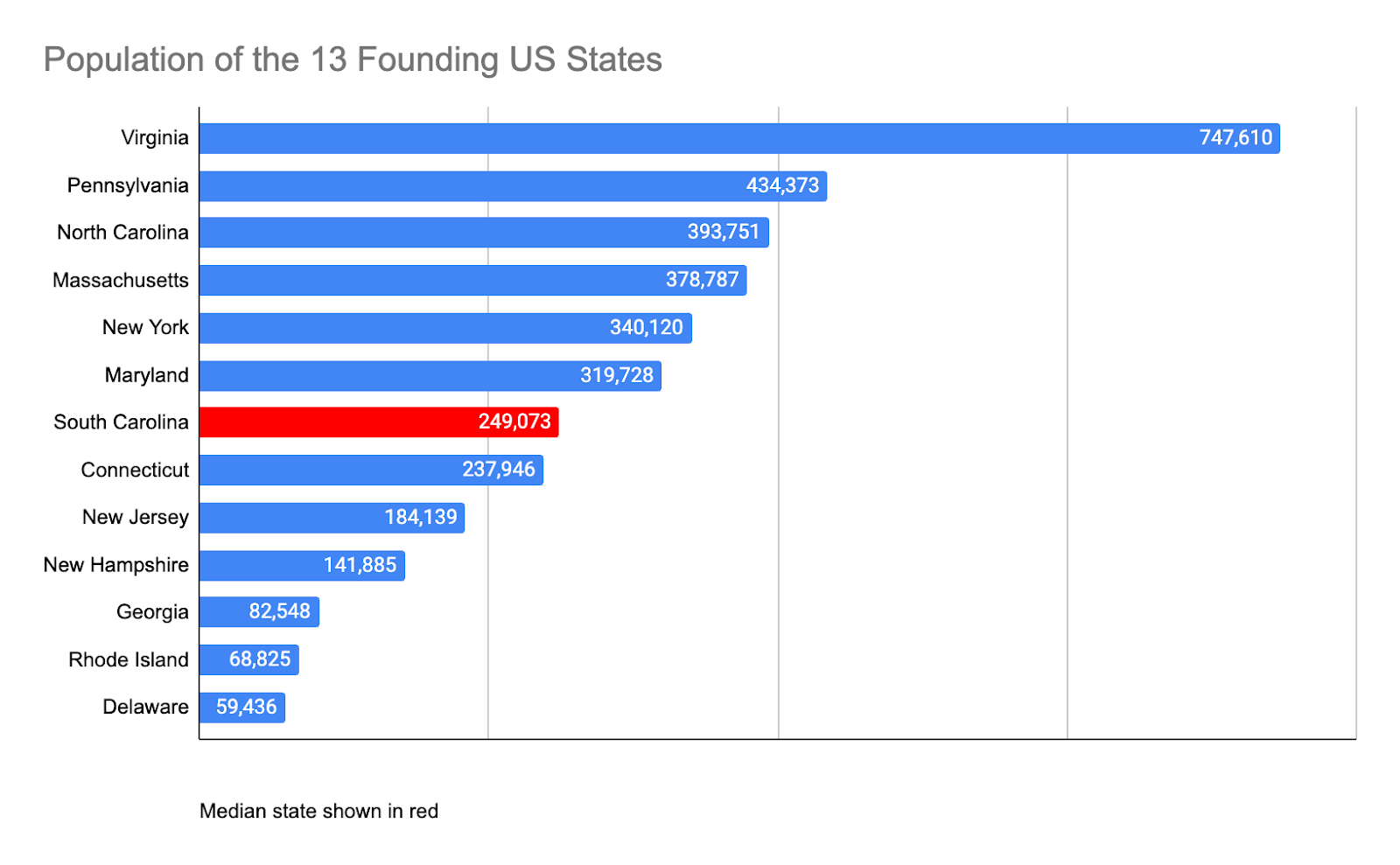

End of civics refresher. In 1787, 3.6 million people in the 13 not-yet united states embedded some ideas about federalism in a new constitution. At the time, the population looked like this.

Notice the proportions. Virginia, the biggest state, is thirteen times larger than Delaware, the smallest and three times larger than South Carolina, the median state. This is a rough measure of the cost that federalism imposed on the large states and the benefit that it conferred on the small ones. A senator from Virginia represented 13 times more people than his counterpart from Delaware and three times more than his colleague from South Carolina.

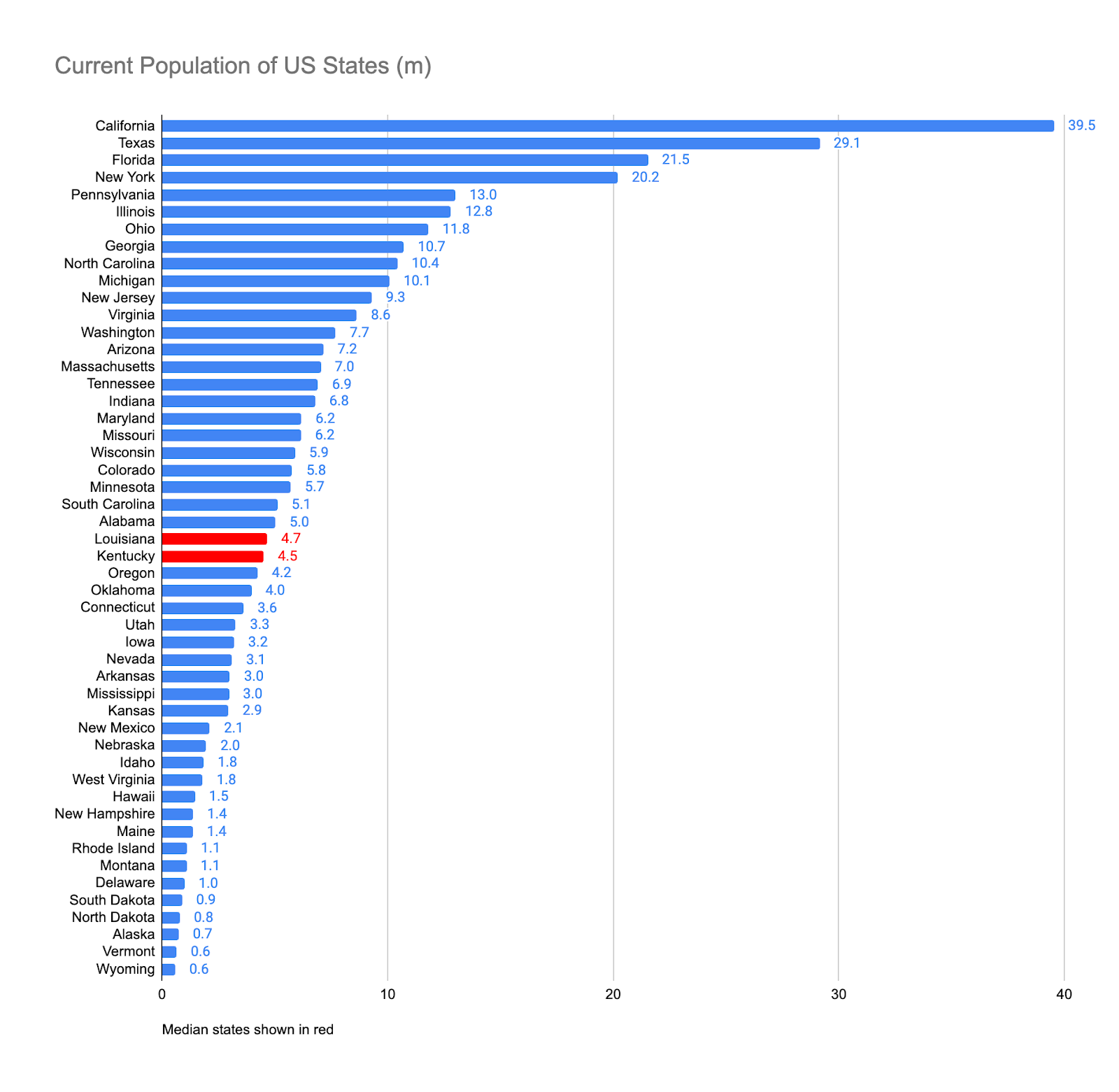

The white gentlemen who crafted the constitution did not anticipate a country that would be nearly one hundred times bigger some 237 years later. Now we look like this.

Consider the proportions again. California is the new Virginia and Wyoming the new Delaware. But a senator from California now represents 69, not 13, times more people than the senator from the smallest state. California is not three times bigger than Louisiana or Kentucky, the current median states – it is almost nine times bigger.

So what? The problem is that massive population discrepancies between states undermines federalism. I’m Californian, so I know that citizens of a state that is nine times bigger than the median enjoy much less local autonomy. We have a harder time trying new approaches. Power is more concentrated and participation is diminished. Diverse communities get homogenized.

What if we returned to something like our original proportions? Remember that the largest state, Virginia, was three times larger than the median state. So we would require any state to divide when it hit 14 million people – triple the population of our median states, Louisiana/Kentucky.

What would this mean? California would become four states, Texas three, Florida and New York two each. We would gain seven new states, all of them large (around ten million people each) but not gigantic. If Pennsylvania, Illinois, or Ohio get much bigger, they would need to divide – but these are slow growth states at the moment. (Plus the addition of seven large states would enlarge the median state, so the threshold for dividing would increase to about 19 million.)

This is not going to happen. To understand why, let’s take a quick look back. Historically, states that have divided have done so as territories before they joined the Union or as new, undeveloped states with little in the way of shared infrastructure to divide up.

Several states divided before they joined the Union.

North and South Carolina. During the colonial period, North and South Carolina were part of the Province of Carolina. Northern Carolina was more rural and developed slowly, with small subsistence farms and few large plantations. Southern Carolina rapidly developed a wealthier economy driven by rice and indigo plantations, slavery, and trade through the port of Charleston. By 1729, they were administered as separate colonies, so they joined the Union as separate states.

Vermont and New York/New Hampshire. Vermont’s path to statehood was complicated by territorial disputes between New York and New Hampshire. Both colonies claimed the area that is now Vermont. During the American Revolution, settlers in the disputed territory declared an independent Republic of Vermont. For 14 years, Vermont functioned as a self-governing republic, with its own constitution, government, army, and currency. Finally, in 1791, Vermont was admitted to the Union as the 14th state, after resolving its land disputes with New York.

North and South Dakota. The Dakota Territory was originally a large, unified region that included parts of present-day Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska. Thanks in part to railroads, many more people settled in the southern part of the Dakota Territory, leading to tensions between north and south. The Republican Party controlled Congress in the late nineteenth century and was interested in creating more states from the Dakota Territory to strengthen its influence in the Senate. North and South Dakota were admitted as separate states in 1889. When he signed the proclamations admitting the two new states, President Benjamin Harrison deliberately shuffled the papers. To this day nobody knows which state was admitted first.

New Mexico and Arizona. The New Mexico Territory originally included what is now New Mexico and Arizona. In 1863, the territory was split, creating the Arizona Territory. Both territories became states in 1912.

A few states separated either right after they joined the Union or during the Civil War.

Kentucky and Virginia. During the late 18the century, Kentucky County was part of Virginia. As settlers moved into the region, they became frustrated with the difficulty of governing the distant frontier from Richmond, Virginia. Kentucky residents sought independence from Virginia to manage their local affairs more effectively. After several petitions to the Virginia legislature, an agreement was reached for Kentucky to become its own state. It was admitted in 1792 as the 15th state of the Union.

Maine and Massachusetts. Originally, the territory of Maine was part of Massachusetts, even though it was geographically separated by New Hampshire. Maine residents understandably felt disconnected from their state government. Maine was admitted to the union as part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave state in an effort to maintain a balance between free and slave states.

West Virginia and Virginia. West Virginia split from Virginia due to geographical, economic, and political differences at the time of the Civil War. Western Virginia was coal country and opposed to slavery, while eastern Virginia was dominated by large plantations built by enslaved people. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Virginia voted to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. But delegates from 40 northwestern Virginia counties rejected Virginia's decision to secede and began the process of forming a new, separate government loyal to the Union.

The Union supported the creation of West Virginia to strengthen its position in the war. West Virginia's location along the Ohio River and its railroad lines made it strategically important to the Union, so West Virginia was admitted to the Union as the 35th state in 1863.

The two largest states in the union, Texas and California, have an interesting and contrasting history of division.

Texas. Following its successful rebellion against Mexico, Texas was an independent nation from 1836-1845. At the time, Texas was massive, covering parts of present-day New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming. The Republic of Texas even opened overseas embassies. The ones on St. James Street in London and at 1 Place Vendôme in Paris are still memorialized.

From the start, the Republic of Texas was so big that southern politicians wanted to admit it as multiple slave states to strengthen pro-slavery forces in Congress. Anti-slavery Republicans opposed this of course, but it enabled Texas to negotiate favorable terms for joining the Union. These included retention of its vast public lands (other states had ceded their lands to the federal government upon admission). Texas also bargained for the right to divide into five states – rights that, unlike in California, have never engendered widespread public support. Nobody wants to mess with Texas.

California. In contrast, many Californians have long believed that the state is too big and should be broken up. Over the years, Californians have made more than 220 attempts to divide our state. These efforts began the moment California joined the Union in 1850. In 1859, the state legislature approved the Pico Act, a plan to split the state in two. Southern California was to become the new state of Colorado (unrelated to the current state). Voters in Southern California approved the measure but Congress never acted on it due to the onset of the Civil War.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, California's geographic and economic diversity fostered tensions. Northern California has always differed sharply from the southern part of the state, which has historically been more conservative and focused on entertainment and defense. Since World War II, there have been several serious efforts to divide the state.

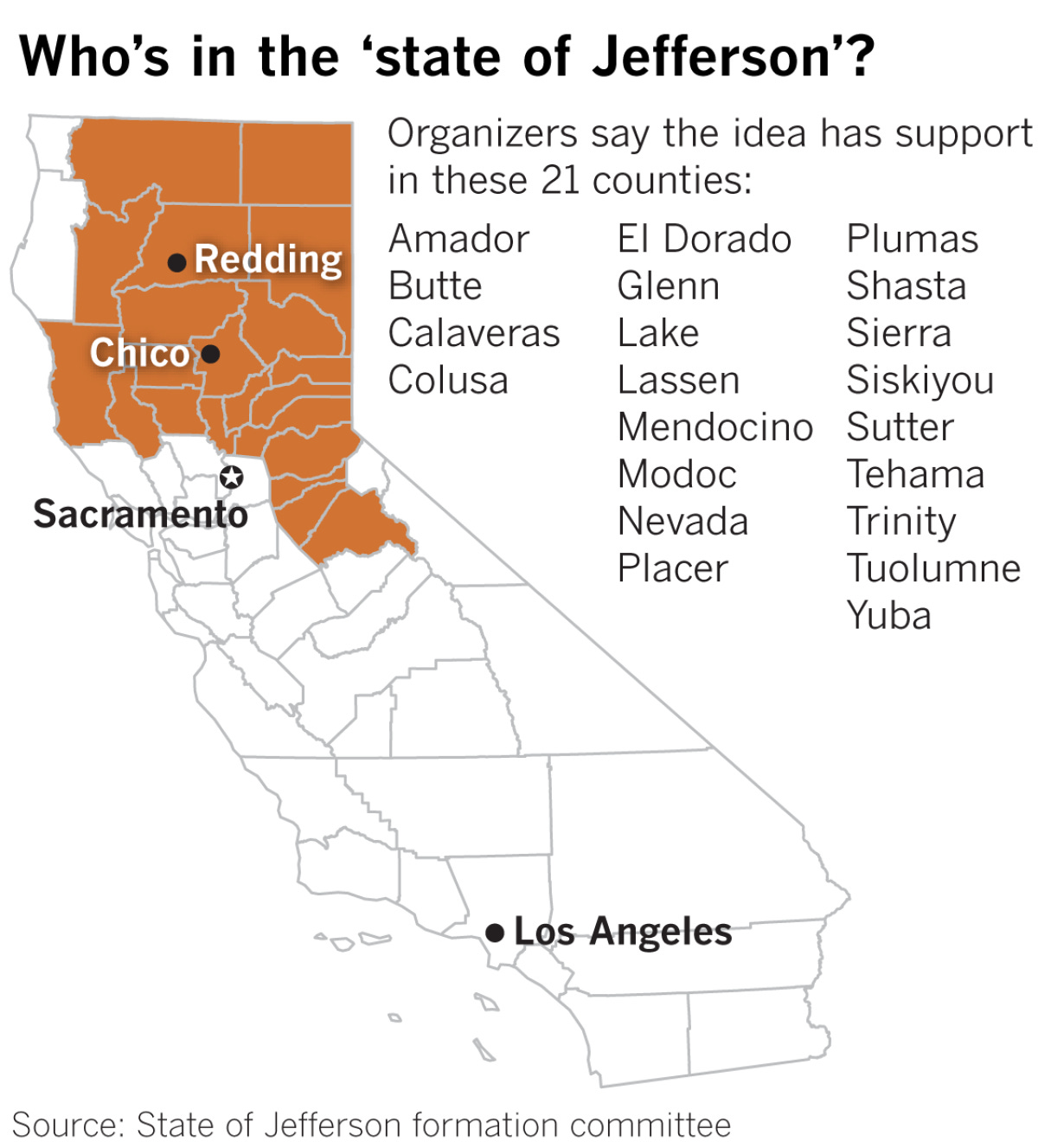

Jefferson. In 1941, citizens in the northern part of California and southern Oregon, frustrated by what they saw as neglect from their state governments, proposed the formation of a rural and more conservative state called Jefferson. The idea was to create a state encompassing northern California counties like Siskiyou and Del Norte, and parts of southern Oregon. The State of Jefferson movement gained some momentum, but it was halted by the onset of World War II, which diverted attention and resources away from domestic issues. Nonetheless, the idea of "Jefferson" has remained in the cultural and political landscape of the region.

Stan Statham. Dividing California was an occasional topic during the 1980s and 90s. A 1992 proposal by State Senator Stan Statham called for dividing California into three states: Northern California, Central California, and Southern California. Although it gained some attention, it ultimately failed.

Tim Draper. Venture capitalist Tim Draper has twice led and funded serious efforts to divide the state. In 2009, he proposed to divide California into six states: Jefferson, Northern California, Silicon Valley, Central California, West California, and Southern California. Draper attempted to gather enough signatures to get the proposal on the ballot for a statewide referendum in 2014, but it fell short and did not qualify. In 2018, he returned with a modified plan called Cal 3, which proposed dividing California into Northern California, California, and Southern California. This time, Draper succeeded in collecting enough signatures to qualify the proposal for the November 2018 ballot. However, the California Supreme Court blocked the initiative, ruling that it would require more significant constitutional changes than a simple referendum could accomplish.

Dividing a modern state faces formidable legal, economic, and political barriers. Article IV, Section 3 of the constitution allows for the creation of new states from existing states, but it requires the approval of both Congress and the state’s legislature.

That’s a tall order because any new state affects the balance of Senate and electoral college power. Throughout US history, these concerns have always dominated any debate over admitting a new state (this is why Washington, DC is not a state). Most state governments have historically opposed efforts to divide their state, and gaining approval from a Congress anxious to preserve Senate and electoral college equilibria would be difficult. If the politics of approval were overcome, the task of dividing a large state’s debt, political districts, water systems, roads, university campuses, offices, and other public infrastructure is complex, costly, and massively divisive.

Although there are compelling reasons to divide big states, the politics and the costs of doing so make most plans to do so a nonstarter. For good reason, no American state has divided itself since the Civil War.