We Made Ballots Secret. Why Not Do the Same For Campaign Contributions?

As the 2024 campaign heats up, it's time to revisit "Voting with Dollars" by Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres

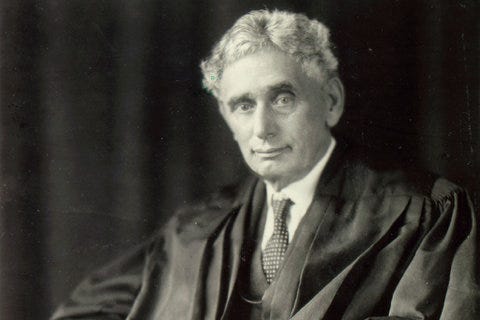

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis loved transparency, and famously claimed that “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants”. It seems so intuitive that full disclosure is our goto antiseptic in matters corporate and regulatory. Worried about crooked managers? Increase disclosure requirements. Concerned about administrative rulings taken behind close doors? Require open hearings and allow for public comment. Want to know who is paying for your Congressman? Require full disclosure of all campaign contributions. Sunshine Laws are based on the belief that in the bright light of day, government and markets will self-regulate.

But we don’t always want market behavior in public life. For example, for most of US history, voting was public, not private. Voting by secret ballot was unheard of until Tasmania introduced it in 1856. It remained highly controversial for many decades thereafter and was known in the US as the “Australian Ballot”. No US President was elected by secret ballot until Grover Cleveland in 1892. One suspects that our portly President promptly noticed that nearly every voter he met assured him that “I voted for you” and learned to take such statements with a grain of salt.

Secret ballots worked because it restricted market behavior — namely the buying and selling of votes. Once votes were secret, buying votes no longer made sense because the buyer had no way of knowing whether the seller had honored the deal. Politics became more democratic – meaning that election outcomes reflected voter sentiment more and market power less. Today it is unimaginable that we would ask citizens to elect leaders in open meetings (although the tradition persists in some caucuses and we rightly insist that our legislators usually vote publicly in order to hold them accountable).

Of course just because politicians could no longer buy voters did not mean that voters could no longer buy politicians with campaign contributions. But those who wished to reduce the role of private financial contributions on public officials nearly always resorted to Brandeisian transparency. They made fundraising disclosure into a cornerstone of campaign finance reform. There is a powerful argument that this is precisely backwards and that politicians should no more know who donates money to their campaign than they know with certainty who votes for them.

Should campaign contributions be as secret as votes are? In Voting With Dollars, Yale legal scholars Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres outline a simple law under which candidates could only receive funds from a blind trust managed by the federal government. Citizens, companies, parties, PACs, and lobbies could all contribute to any cause, party, or candidate they wish – but their contribution would pass through the blind trust. Candidates would receive the money but could no more verify the source of their contributions than they they can today validate with certainty which citizens voted for them.

At the same time, the government would provide each voter with “patriot dollars” — which each voter could donate to the cause or candidate of their choice. People would be free to make additional contributions, but these like all campaign gifts would be made anonymously via the federal trust.

This would powerfully change a donor’s expected return on investment because no politician can repay a contribution they cannot identify. Once again, we use secrecy to reduce market behavior: a candidate that cannot identify the source of their campaign funds cannot sell political influence. Moreover, the need for politicians to compete for the Patriot dollars will balance out the malign influence of the Electoral College. Those of us overlooked voters in electorally solid red or blue states will suddenly matter again.

Of course lots of citizens and advocacy organizations would assure politicians of their undying financial generosity. Politicians would treat these assurances with the same warm but secretly skeptical smile they offer people who claim to have voted for them. We would weaken the market for politicians just as we once weakened the market for votes. Our republic would never look back.