Charles Grandison Finney was a renowned and eccentric nineteenth-century evangelist whose traveling revival meetings attracted enormous crowds. He was a utopian idealist who took the unprecedented step of encouraging women to pray aloud alongside men in public gatherings. A devoted abolitionist, he denied communion to slave owners and advocated for equal education for women and African Americans. When Oberlin College appointed him as its second president, Finney welcomed students of all races and genders and transformed the campus into a station on the Underground Railroad. He may have been the last president of Oberlin who was more radical than his students.

As Civil War storm clouds gathered in 1860, Finney admitted his sister’s granddaughter, Frances “Eva” Copeland, to Oberlin. Eva was my great-great-grandmother and became one of the first women in America to earn a four-year college degree. Mary Jane Patterson was two years ahead of her and the first Black woman to earn a bachelor's degree in the United States. Thanks to Eva, I am a fifth-generation college graduate on my mother’s side. My dad was the first member of his family to graduate from college.

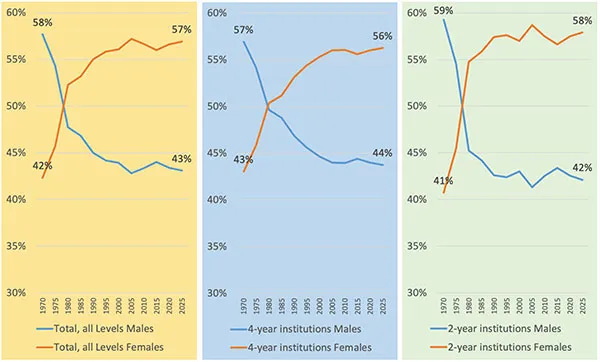

By 1950, when my mother was in college, approximately one-third of college students were women. When I entered college in 1970, over forty percent of my classmates were female, thanks to generations of women who fought hard for access to colleges historically reserved for men. This was not an easy transition (ask my wife, who was in the first class of women at a college that had been all-male for 179 years). This was a genuine civil rights victory fought over many decades, and every American should celebrate it.

Today, nearly sixty percent of college students are women. The United States has 8.9 million women attending college and 6.5 million men. Women across all racial groups and in every modern country are more likely than men to enroll in college, earn solid grades, and graduate. The gap is particularly pronounced among Black, Latino, and working-class white men.

Women now earn most graduate degrees. The share of doctoral degrees going to men dropped from 73% in 1980 to 43% in 2022. Men are now the minority of MDs, and male law school enrollment is at a 50-year low.

Is the feminization of higher education a problem?

Some argue that the ratio of men to women on campus is irrelevant. They assert that education reflects individual choices and efforts, so men’s lower enrollment in college is a rational response to labor market options that include learning a trade, starting a company, or pursuing technology paths that don’t require a college degree.

This is not entirely wrong. We should neither expect nor require everyone to attend college to earn a middle-class living. We unquestionably need better career technical education for men and women. I wrote about this in February.

On the other hand, if men are systematically underperforming and disengaging from higher education, that is a sign of institutional failure, not just individual drift. Growing the share of non-college men reduces their earnings and has knock-on effects, including worse health, higher mortality, and less stable families.

The defection of men from college campuses has accompanied a collapse in public confidence in higher education. When Gallup first measured it in 2015, 57% of respondents had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in American colleges and universities. Only 10% expressed “little or no confidence”. Subtracting, America’s net confidence in higher education was 47%. Today, only 36% express a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in higher education, and 32% have little or no confidence. Our net confidence in colleges has fallen from 47% to 4% in ten years – an astonishing drop for an industry widely considered one of our crown jewels. Tuition has risen four times faster than overall inflation since 2000, reducing access to higher education and undoubtedly contributing to this sentiment.1

Some writers assert that this loss of public confidence is the direct result of the feminization of higher education. They argue that higher education was deemed prestigious and important when college students were predominantly men. However, now that the majority of college students are women, college is suddenly unnecessary and unworthy. They cite the example of male-dominated occupations such as teaching, clerical work, and human resources, which saw a decline in pay and status as they became feminized. They contend that a similar phenomenon is occurring in colleges and universities.

This argument is flawed. A college student is not an occupation. Even if it were, many occupations feminized without losing status or pay, especially when skill demands increased. In 1980, veterinarians, pharmacists, attorneys, humanities and social science professors, public sector managers, and physician assistants were all predominantly male professionals. Today, these occupations are majority female and enjoy higher median compensation after adjusting for inflation.2

We are failing boys and men.

Women are not the problem. We are failing our boys and young men. We hold more boys back in school, diagnose more of them with ADHD, and suspend them more often. Schools punish behaviors more common in boys: restlessness, risk-taking, aggression, and noncompliance, especially in institutions with zero-tolerance discipline policies. Boys are more likely to score below average in reading and writing, which affects their college readiness. They are far more likely to drop out of high school. The lack of male teachers and mentors appears to contribute to alienation from school, particularly for boys of color.

The skyrocketing cost of college affects both women and men, but it amplifies cultural messages to men that education is not for them. Many blue-collar men do not see a clear benefit to college, especially if they cannot access selective institutions or lucrative computer science and engineering majors, which remain predominantly male. Many working-class communities view feminized colleges as irrelevant to male-coded aspirations such as action, leadership, and autonomy. Although the male breadwinner model has collapsed, many young men lack an empowering, future-oriented alternative life narrative that college provides. Young men retreat into online gaming, gig work, day trading, sports betting, or trolling.

Our high schools and community colleges lack the resources to support boys and men as a group. Unlike girls and underrepresented minorities, boys from disadvantaged backgrounds receive minimal institutional support aimed at college readiness. There is no national initiative to understand or address male educational disengagement. An administration that thrives on chaos and toxic masculinity is very unlikely to initiate one.

Solutions

Complex social problems never yield to simple policy interventions, but we can take some obvious steps to improve the education of boys and men.

Invest early. The average American and most high school graduates read at a 7th- to 8th-grade level, making further education difficult if not impossible. Both math and reading scores have hit new lows, with boys scoring significantly lower than girls. This problem requires much more than volunteerism, but relying on volunteer mentors, the nationwide Reading Partners program has dramatically improved reading scores for low-income students and enjoys a high success rate with boys. Likewise, we should expand mentorship models like Big Brothers and Big Sisters, which continue to hit meaningful literacy improvement goals.

Rebuild career and technical education. Many of these career pathways require a year or two of community college, which are the underappreciated mobility engines of higher education. For example, CareerWise Colorado connects high school students to IT, finance, and advanced manufacturing apprenticeships.

Create federally recognized credentials. We need federally recognized, portable credentials to create job market liquidity and encourage mobility, especially for high-skill trades and tech roles. I discussed this three weeks ago.

Publicize earnings and career paths that don’t require a four-year degree but lead to middle-class outcomes. Many families with no tradition of college education have no way to discover that the median electrician in the Bay Area now earns a six-figure income.

Expand college models that work for men. We need to experiment, test, and discover educational models that work for different groups of men. For example, commuter and hybrid programs that serve men balancing work, family, or economic uncertainty seem to work in some regions. Georgia State University uses predictive analytics and intensive advising to improve male student retention, especially among first-generation students.

Test predominantly men’s colleges. Women’s colleges played an essential role from roughly the 1870s to the 1960s by providing educational opportunities when prestigious colleges and universities either did not admit women or severely restricted their numbers.

These schools should test new pedagogies outside the classroom, beyond the standard four-year-or-nothing approach. Modular credentials, tailored pedagogy, online hybrid programs, male mentorship, and community or company-based models might re-engage alienated men. If well-led and structured, they might reshape masculinity around achievement, responsibility, and social connection, rather than just competition or withdrawal. These schools should highlight male role models in education, healthcare, and civic life who defy outdated gender scripts, much as historically Black colleges have always done.

This idea is unlikely to scale (women’s colleges didn’t). Most men’s colleges failed decades ago due to a lack of demand. The root problems—disengagement from schooling, economic alienation, and lack of purpose—run deeper than campus culture. Nonetheless, some men might benefit from predominantly male colleges, just as some women benefit from women’s colleges.

Gather the data we need for accountability. To determine whether we are reaching men statistically unlikely to attend college, we should require institutions receiving federal aid to report outcomes and disaggregate them by gender and socio-economic status. At the same time, we should fund longitudinal research on the life outcomes of non-college men to better understand what causes them to engage and disengage with school.

Nobody should treat the male college enrollment gap as nostalgia for past gender roles and the exclusion of women. We must invest systematically in pathways that reconnect young men to opportunity, purpose, and belonging by treating the education of boys and men with the same seriousness and evangelical fervor that our ancestors once used to expand educational access for women.

Musical Coda

I grew up at one end of Whittier Boulevard, Tom Waits at the other. We both remember cruising down the Boulevard past Bob’s Big Boy Burgers on Saturday night.

Over the past twenty years, tuition and fees at public four-year institutions have increased by 141% and by 181% at private four-year institutions. Over the same period, the Consumer Price Index rose by about 39%.

The general claim that not every profession that grows its share of women suffers income losses is straightforward to verify. This specific list of occupations can be validated using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ "Women in the Labor Force: A Databook," which includes data on women's employment by industry and occupation. The Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS) also provides valuable insights into occupational distribution by gender.

Caveats: If you take the year 2000 or 2010 as the starting point instead of 1980, many of the occupations listed here have median incomes that have not kept up with inflation (others may have done so). Also, comparisons like these are fraught, since the actual work of many of these jobs has changed dramatically since 1980.

As you know, the disaffected male population has powered Trump's political base.

The focus on women's equality may have had unintended consequences for men. Interesting how complex systems respond to interventions in unanticipated ways.