When Liberal Instincts Produce Conservative Results

Three strong books and an important article on how progressives can build again

Progressivism's deepest instinct is to regulate, redistribute, and empower the weak. We like our markets safely encased in rules. We happily take from market winners to support everyone else. "People over profits” and “power is to the people” are so ingrained as to no longer require campaign buttons.

Three recent books and an important article document the limits of these impulses. Our preference for regulation led us to ignore the need to build and grow. Our nervousness about wealth creation made us suspicious of technology and the companies that create it. We downplayed the vital importance of geographic mobility and merit-based achievement to non-college citizens. We empowered minorities to thwart the majority will.

The authors each bring a unique angle to the blind spots that have led Democrats into our political cul-de-sac. Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity by Yoni Appelbaum is the stand-out contribution because it focuses sharply on the mobility of non-college Americans. Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress—and How to Bring It Back by Marc J. Dunkelman tackles the question of government competence: why can we not get big things done anymore? An insightful article, Minoritarianism Is Everywhere, by Steve Teles, points out that progressives frequently empower minorities to overrule majority sentiment. The widely-acclaimed Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson examines how environmental rules have led to far less housing and cheap energy than we need. Each book explores how liberal instincts have produced illiberal results. These five authors are smart policy folks who write well and deserve a wide readership.

Stuck

In Stuck, Atlantic Senior Editor Yoni Appelbaum examines the decline in geographic mobility in the United States. Appelbaum documents how property owners impeded social mobility and economic opportunity in America. He traces the historical evolution of policies that favor the status quo, including restrictive zoning laws initially designed to reinforce racial segregation during Reconstruction. These laws evolved to limit housing development, particularly in affluent areas, leading to increased housing costs and reduced access to high-quality neighborhoods.

Applebaum cites Raj Chetty’s compelling research showing that a child who moves from a low-opportunity to a high-opportunity neighborhood earns about 31% more as an adult, and every additional year spent in a better neighborhood corresponds to about 4% more adult income. He vividly describes the nineteenth-century practice of moving day – a giant game of musical houses.

“Moving Day was a festival of new hopes and new beginnings, of shattered dreams and shattered crockery—“quite as recognized a day as Christmas or the Fourth of July,” as a Chicago paper put it.

“It was primarily an urban holiday, although many rural communities where leased farms predominated held their own observances. And nothing quite so astonished visitors from abroad as the spectacle of so many people picking up and swapping homes in a single day. For months before Moving Day, Americans prepared for the occasion. Tenants gave notice to their landlords or received word of the new rent. Then followed a frenzied period of house hunting, as people, generally women, scouted for a new place to live that would, in some respect, improve upon the old. “They want more room, or they want as much room for less rent, or they want a better location, or they want some convenience not heretofore enjoyed,”

“The Topeka Daily Capital summarized. These were months of general anticipation; cities and towns were alive with excitement. Early in the morning on the day itself, people commenced moving everything they owned down to the street corners in great piles of barrels and crates and carpetbags, vacating houses and apartments before the new renters arrived. “Be out at 12 you must, for another family are on your heels, and Thermopylae was a very tame pass compared with the excitement which rises when two families meet in the same hall,” warned a Brooklyn minister. The carmen, driving their wagons and drays through the narrow roads, charged extortionate rates, lashing mattresses and furnishings atop heaps of other goods and careening through the streets to complete as many runs as they could before nightfall. Rowdy youths burned the old straw used for bedding in the streets, and liquor lubricated the proceedings. Treasure hunters picked through the detritus in the gutters. Utility companies arrived on the scene and scrambled to register all the changes. Dusk found families settling into their new homes, unpacking belongings, and meeting the neighbors.

“In St. Louis, the publisher of a city directory complained that a third of the families moved each year, and estimated that over a five-year span only one in ten remained at the same address. “Many private families make it a point to move every year,” the Daily Republican of Wilmington, Delaware, reported. In some places, in fact, it was staying put from one year to the next that was seen as unusual. One story, perhaps apocryphal, told of a woman so ashamed not to be moving that she shuttered her windows so her neighbors would assume she had left. Moving Day, the humorist Mortimer Thomson quipped in 1857, had become “a religious observance not [to] be neglected by any man on pain of being considered an infidel and a heathen. The individual who does not move on the first of May 1 is looked upon…as a heretic and a dangerous man.”

Appelbaum shows that reduced mobility hinders an individual’s ability to get a better job. This is not small potatoes. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimated that if highly productive metropolitan areas like New York, San Francisco, and San Jose had accommodated more residents since 1964, the U.S. GDP could have been approximately $2 trillion higher by 2009. This translates to an additional $8,775 annual income for each American worker.

High housing prices that constrain mobility have disproportionately affected lower-income workers. For example, a lawyer moving from the Deep South to New York City might see their income increase by 40% after housing costs, and a janitor making the same move would be 7% worse off due to exorbitant housing expenses. This contrasts sharply with 1960 when such a move would have resulted in a 70% income gain for a janitor.

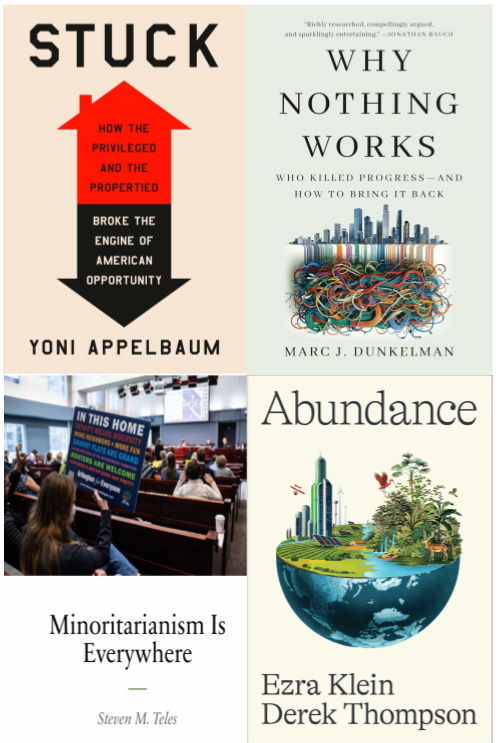

Applebaum is less clear about policy or cultural solutions than I’d have preferred. He advocates for three principles: tolerance, consistency, and abundance without telling us whether to repeal or reform NEQA or similar bills that enable incumbents to prevent the construction of housing and infrastructure. He also neglects the impact of restricted mobility on the electoral map, which is very bad for status quo Democrats, as this projection of 2030 congressional reapportionment makes clear.

Why Nothing Works

Marc J. Dunkelman’s book, Why Nothing Works, contrasts two progressive instincts: a Hamiltonian instinct to centralize power and get things done, Robert Moses-style, with a Jeffersonian instinct for local town-hall democracy. He argues that at the moment, we have the worst of both – a Jefferson-inspired “vetocracy” that empowers affluent activists to obstruct construction and a progressive deep-seated mistrust of Hamiltonian centralized authority. Dunkleman, a researcher at Brown, contends that while conservatives share some blame, progressives have inadvertently contributed to an overemphasis on limiting government power. He grounds his book on a stronger understanding of history than the others reviewed here.

Historically, progressives championed robust governmental initiatives, resulting in monumental achievements like the Tennessee Valley Authority and the interstate highway system. However, since the 1960s, a cultural shift toward decentralization and skepticism of a corporate “establishment” have led to reforms that, while aiming to prevent abuses of power, have also hamstrung the government’s capacity to act decisively. FDR could not build the TVA today.

Dunkleman argues that progressives either restore our ability to deliver public goods effectively or risk seeing gridlock and diminished trust in public institutions open doors to Trump/Musk-style populists who exploit frustration with government inefficiencies to burn instead of build. He wrestles less with the underside of this problem — how government incompetence self-reproduces by repelling the talent and discouraging the risk-taking that any revitalization requires. (He should write with Jen Pahlka, whose excellent book Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better I have only skimmed and perhaps should have included here.)

Minoritarianism

Steve Teles’ article Minoritarianism Is Everywhere focuses on one of the causes of the tension Dunkleman describes – the pervasive influence of empowered minority groups. Teles challenges the prevailing narrative that attributes threats to American democracy solely to right-wing minority rule. He argues that minoritarianism—where decision-making power rests with a minority—pervades various aspects of governance, often due to actions from the center-left over the past half-century. He cites NIMBYism, public sector labor unions, occupational licensing boards, and the governance of higher education as examples of dysfunctional minority rule. Teles argues that “minoritarianism” (an eight-syllable word in desperate need of a thesaurus) undermines democratic principles and leads to policy outcomes that do not reflect majority preferences.

Abundance

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book examines the paradox of modern American liberalism: Policies that once delivered results now get in the way. Regulations that protected and improved the environment have, during the past three decades, led to shortages in housing, infrastructure, and technological innovation. Their proposed “abundance agenda” values outputs over inputs, meaning results over process. It aims for “a liberalism that builds.” This is the most anticipated and widely discussed of these books and, in many ways, the least satisfying.

Klein and Thompson are accomplished journalists who avoid right-coded terminology like deregulation and regulatory overreach – but that’s what their book is about. They detail how environmentalists have weaponized laws designed to clean the air or preserve species to block affordable housing and renewable energy.

For example, Congress passed the National Environmental Quality Act to ensure the environmental friendliness of public spending. However, the courts unexpectedly applied these rules to any private construction that requires a building permit. This decision handed affluent homeowners a powerful tool to block housing, transit, or renewable energy generation—goals that most progressives support. They describe public spending that contains “everything bagel” provisions to favor small, minority, or women-owned businesses, veterans, unions, child care, etc. These goals may be individually desirable but can also be collectively paralyzing. The EV charging stations, high-speed rail, new housing, or broadband services we fund never get built or cost blue states much more than red ones.

They show that liberals have shifted from building to blocking. The country is short some seven million housing units, and the shortage is worse in blue states and much worse in blue cities. Moreover, the bluer the city, the worse the shortage. In 2000, New York City was home to eight million people. In 2023, the population was 8.2 million, meaning that America’s most important city stood still as its housing costs tripled.

Californians understand this. We build so little housing or green energy that many Californians are fleeing to Texas, which creates plenty of both. Lawsuits and environmental challenges have consumed the $33 billion Californians approved for high-speed rail between San Francisco and Los Angeles. The money we authorized for a high-speed SF-LA train in 2020 might buy us a train between Bakersfield and Modesto in five years. If California's high-speed rail ever launches, it will be an embarrassing monument to blue-state paralysis.

An excellent chapter (almost surely written by Thompson) describes how this focus on process instead of results has affected scientific research, except in moments of crisis. During World War II, the federal government moved with purpose and alacrity. During Project Warp Speed, the historic effort to create a Covid vaccine that saved hundreds of thousands of lives, it did the same.

He describes the valor of Kati Karikó, who pursued mRNA technology for over three decades despite being denied federal funding so often that the University of Pennsylvania demoted her. Her innovations enabled Warp Speed to create, manufacture, and distribute a life-saving Covid vaccine in record time. The project helped end the Covid pandemic, but the Biden Administration shamefully buried it and removed all public references to Warp Speed. Meanwhile, Team Trump is embarrassed by its success, thanks to its embrace of knuckle-dragging anti-vaxxers. The Hungarian-born Karikó, meanwhile, won a richly deserved Nobel Prize in Medicine and global acclaim for a “shot that saved the world.”

As the most prominent of these three books, Abundance is coming in for a shower of criticism from the Warren/Biden left (Biden ran like Joe but, after 2022, governed like Elizabeth, and voters smelled it). The essence of the critique is that “We prefer to regulate, redistribute, and empower the weak. And we hate corporations.” If abundance requires entrepreneurship, they oppose it. This is blindingly stupid: “corporate domination” cannot explain why Houston builds more housing than San Francisco. As they often do, Noah Smith and Matt Yglesias summarize the fight well.

Abundance contains some odd omissions. The book is strangely silent on health care and education – two areas the authors know well where liberals have also driven costs higher by subsidizing demand while restricting supply. They omit the impact of high housing prices on working families and politics (perhaps because Thompson knew that his boss, Yoni Applebaum, was writing a book on the subject). Klein and Thompson want local democracy to stop protecting incumbents. Still, they do not confront the tension at the core of housing politics: the sometimes accurate belief by existing homeowners that restricting new home construction makes them richer. Since a large portion of their net worth is in their homes, NIMBY incumbents are vastly more committed to restrictions than unrepresented future residents are to building new homes.

Each of these writings is practical, almost managerial, in outlook and tone. They start less from ideology than from results. Like the great Chinese reformer Deng Xiaoping, they ask not whether a cat is black or white, but whether it catches mice. They capture the spirit of Gretchen Whitmer’s “Fix the Damn Roads” gubernatorial campaign and Josh Shapiro’s relentless focus on rapidly restoring the I-68 bridge collapse. This focus on getting things done is a light that can help guide Democrats out of the political corner into which we blissfully painted ourselves.

Links

Yoni Applebaum’s Stuck. Read Applebaum’s excellent summary article in The Atlantic here. The Los Angeles Times did a good review here.

Dunkleman’s Why Nothing Works. Good podcast review here and a Niskanen interview here. A strong New Yorker review of Dunkleman as well as Klein/Thompson here.

Klein and Thompson’s Abundance. Read the articles that led the authors to collaborate here and here. Excellent reviews by Noah Smith here, Jersusalem Demsas here, and Matt Yglesias here. Terrific interview of Ezra Klein by a skeptical Tyler Cowan here. Skeptical, Hewlett-financed reviews in the Washington Monthly here and here.

CODA

Hey Marty, have you read Why Liberalism Failed? Apparently it's a pretty influential book amongst the right wingers and I thought the basic thesis was simple (maybe simplistic) and therefore pretty powerful. Paradoxically, the author notes that liberalism's "control of nature" is leading to environmental disaster, but then doesn't address that maybe regulation is needed to manage that.