This is a Sunday post because it is longer and more leisurely. It is not typical and it’s not for everyone. It concerns my odd lifelong passion for mechanical tool watches. It turns out that good watches come with good stories.

People have always tracked time. Early humans cared more about seasons than sundowns, so calendars were more important than clocks. By 1500 BCE people were using sundials (mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, so time advanced “clockwise”). Today timekeeping is so thoroughly baked into every digital device that we barely notice it.

Time is a social construct and timekeeping a political one. When a public clock came to town, the priest, mayor, or business owner set it to local noon and began to coordinate worship, navigation, commerce, finance, and warfare. Eventually pocket watches and railroads that required standard times eroded the power of church and municipal timekeepers. Once workers acquired pocket watches, bosses could no longer stretch the workday. Once soldiers got them, military attacks could be far more precise. Watches eroded old information and communication monopolies and helped create new ones, like mobile phones have done more recently.

Pocket watches emerged during the seventeenth century but mechanical wristwatches did not become popular for men until the First World War. They were short-lived: nobody needed a mechanical wristwatch in 1910 and nobody needed one seventy years later after quartz took over. But during my early years, men and women in every field wore mechanical wristwatches that reflected unique designs, technology, stories, and business strategies. To be sure, they also signaled taste, status, and style a bit like jewelry does. Unlike jewelry however, these watches are tools and meant to be used.

The technical complexity of mechanical watchmaking and the growing demand for nice watches spawned an industry of specialized designers, engineers, managers, component suppliers, marketers, and watchmakers. Watchmaking can be found everywhere but the industry is concentrated in the valleys north of Geneva, in and around Tokyo, and in a small village outside of Dresden.

All mechanical watches tell time, but some also track the date, day of the week, month of the year, or phase of the moon. Some have tachymeters, slide rules, stopwatches, world clocks, helium escape valves, or alarms. Watch enthusiasts call these add-on functions “complications”. I avoid them.

Good tool watches can, like my childhood Timex, “take a lickin’ and keep on tickin’”. Most are water resistant to at least 100 meters not because anyone dives with them but because it signals resilience. Other features like extreme accuracy, exhibition case backs, and extended power reserves are intriguing, but often add more cost than value. Many users value luminescent dials; I think lume is a cheap party trick played with black lights.

I am not sure why, but I love having complex little machines with hundreds of parts ticking away on my wrist. So here I tell their stories.

The Watchmakers

Every watch starts with a watchmaker who designs the watch and determines the level of craft that goes into making it. They decide not only how the watch looks, but how it is made, priced, marketed, and sold. Is the design simple or flashy? Rugged or elegant? Made by hand or machine? Using in-house or outsourced components? On a bracelet, a strap, or both? Sold by authorized dealers, on a website, or in drugstores?

I profile three kinds of watchmakers. The two most important, Rolex and Seiko, are independent and global. Many well-known watchmakers are part of syndicates like the Swatch Group, Richemont, or LVMH that helped salvage dying brands after the 1970s “quartz crisis”. These conglomerates give their brands access to talent, supplies, and luxury dealers that small independent watchmakers cannot afford. Finally, there are thousands of independent watchmakers all over the world. A few are big, but most are small online sellers. Most outsource their movements, but a few make their own. Each of these companies has a unique history and design philosophy that shape their watches.

Rolex

In 1905, a 24-year-old orphan named Hans Wilsdorf put Swiss movements in British pocket watch cases and sold them in his London store. When he and his brother-in -law partner decided to make their own watches, they realized that “Wilsdorf and Davis” would not look great on a watch dial. Wilsdorf bought out Davis and sought a new brand name that would be easy to pronounce, spell, and remember. Hoping to evoke round, excellent watches, he chose Rolex – a word that like Apple and Coke is today understood almost everywhere in the world.

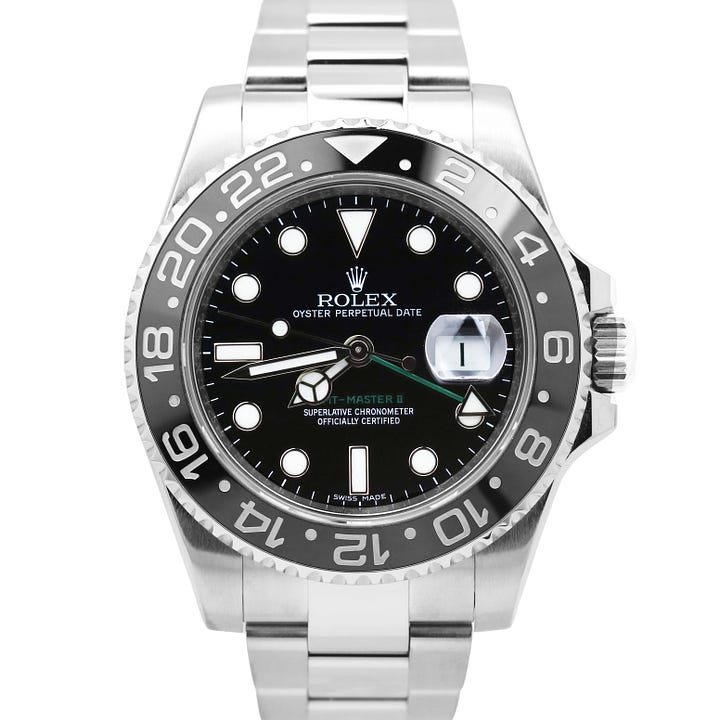

When Wilsdorf moved Rolex from London to Geneva, he was determined to conquer two major limitations of mechanical watches: they needed regular winding and protection from moisture. In 1923, he purchased rights to the first waterproof wristwatch, which had a hermetically sealed case that protected it from water, dust, and other elements. He dubbed it the Rolex Oyster. Today “Oyster” on any Rolex means water-resistant.

In 1931, Rolex introduced the Perpetual rotor, an automatic winding system that uses the natural motion of the wearer's arm to wind the watch. This innovation created automatic watches, which keep running without manual winding. Today “Perpetual” on a Rolex means automatic. These features were widely copied and today most mechanical tool watches are descended from Rolex Oyster Perpetuals.

Rolex is the world’s largest maker of mechanical wristwatches by revenue, in part because its watches are expensive. “The Crown” sells almost a third of all Swiss watches and is four times bigger by revenue than Cartier, its nearest competitor. Rolex sold 1.2 million watches to its dealers in 2023 and could have sold many more. With $10 billion in annual revenue, the average Rolex wholesales for about $8,000. The dealer markup is about 40%, so the average Rolex retails for about $11,000, but the variance is large. Simple watches retail for $5,000 but the price of a bejewelled platinum Rolex is more than $100,000 and some limited models sell for five times that (these are obviously not tool watches). Used Rolexes can fetch stratospheric prices – the record is over $17 million for Paul Newman’s Daytona.

Like Wilsdorf himself, Rolex is both innovative and frustratingly conservative. It has earned more than 500 patents and driven more horological innovations than any other company. Rolex not only pioneered water-resistance and automatic winding, it developed better materials for hairsprings, bezels, luminous paint, anti-magnetism, and shock absorption. It made the first wristwatch certified as a marine chronometer for accuracy and ruggedness. Rolex has always been vertically integrated, running its own steel and gold foundries and manufacturing every part in-house down to the smallest screws, springs, and gears. Rolex designs and fabricates its own bracelets – which are also technological marvels.

Rolex invented modern luxury goods marketing, which has made them conservative. In 1927, Wilsdorf persuaded Mercedes Gleitze to wear an Oyster on a small chain around her neck as she swam the English Channel from France to England. The unscathed watch impressed as many people as the heroic swim, so Rolex and Gleitze made each other famous. She became the first of many athletic brand ambassadors for Rolex.

Rolex pioneered product placement by sending watches up Mt. Everest. They created celebrity endorsements, sponsored athletic tournaments, and pioneered glossy photo advertising. Rolex designed watches for specific professions like scientists, divers, pilots, and soldiers, which created tool watch classifications that collectors still use.

Many enthusiasts admire Rolex watches but dislike the company. The nonprofit Hans Wilsdorf Foundation owns both Rolex and Tudor and has no shareholders to answer to. So instead of simply raising prices when demand vastly outstripped supply in recent years, Rolex decided to ration their watches.

The results have been predictably catastrophic. Used Rolexes now routinely sell for much more than new ones. Like Soviet commissars, dealers they think nothing of asking customers to wait years to buy a new watch, which tempts all manner of corruption. Dealers allocate Rolexes to customers who spend big on other watches or jewelry. Speculators looking for a watch to flip crowd out buyers who want a good watch to wear. Watch enthusiasts despise all of this.

Tudor

Wilsdorf launched Tudor watches in 1926 to make high-quality watches accessible to more people. He equipped Tudor watches Rolex cases but used off-the-shelf movements. Tudor was for many years dubbed “a poor man’s Rolex”.

This never worked. Luxury watches are Veblen goods: demand often rises as prices increase because customers see some Rolexes as status symbols. So a Tudor was a discounted Veblen good, which misses the point. Nobody was eager to tell the world they could not afford the real thing, so customers either bought Rolex or went elsewhere. Born a sibling to Rolex, Tudor found itself an unwanted stepchild. The company resorted to selling unlabeled watches in bulk to the French navy and let its consumer business languish. Tudor completely withdrew from the US market in 2004 – an astonishing failure.

But in the summer of 2013, Tudor came roaring back. No longer the poor man’s Rolex, they launched a stream of innovative designs that filled important gaps in the Rolex lineup. Today Rolex is fifteen times bigger than Tudor by revenue but Tudor watches are admired worldwide. Every day, happy buyers walk out of Rolex dealerships with a smile on their face, a Tudor on their wrist, and several thousand unspent dollars in their pocket.

Seiko

Seiko is perhaps the most innovative watch company in the world and among the most beloved. I respect them enormously.

Seiko’s story began during the 1870s with Kintarō Hattori, a 13-year-old Tokyo kid who loved clocks. In 1881, Hattori followed in his family’s footsteps and opened a watch and jewelry shop that imported Western timepieces. Hattori's shop became popular because he sold watches that could not be found anywhere else in Japan.

In 1892, Hattori began producing his own clocks as Seikosha, meaning "House of Exquisite Workmanship." They eventually shortened the watch brand to Seiko and launched their first in-house pocket watch in 1895. The first Japanese-made wristwatch followed in 1913.

After World War II, Seiko became a juggernaut of horological innovation. They introduced Japan's first automatic wristwatch in 1956, an effective anti-shock device in 1958, and a novel self-winding mechanism called the Magic Lever in 1959. In 1960, the company formed Grand Seiko to design and sell some of the world’s most beautiful and technically advanced wristwatches.

Several amazing decades followed.

1964: Japan's first chronograph and first world-time wristwatch;

1965: Japan’s first diver’s watch;

1967: Seiko won second and third place in the watch accuracy competition at the Neuchâtel Observatory, in Switzerland. The Swiss were so embarrassed by losing to Seiko that they canceled the contest and never held it again.

1969: having caught the Swiss watch industry, Seiko’s next innovation nearly destroyed it. On Christmas Day they launched the world's first production quartz watch. The Astron took a wrecking ball to the staid Swiss watch business.

Although it initially cost as much as a medium-sized car, Seiko scaled up manufacturing and drove costs down until consumers could buy a quartz watch that was ten times more accurate for a tenth of the price of a mechanical timepiece. Along with their fierce rival Citizen, Seiko’s innovations put more than 900 Swiss watchmakers out of business and forced the survivors to retreat into luxury goods manufacturing.

During the eighties, Seiko brought out a wristwatch with a working television (!), the first watch with a record-and-play function, the first wristwatch computer, the first diver's watch with a ceramic case that was water-resistant to 1,000 meters, and the first batteryless quartz watch.

In 1999, Seiko insulted the Swiss once more when they launched the Spring Drive – a mechanical wristwatch with the accuracy of quartz. In more than two decades, the Swiss have never responded. There is still no Swiss watch that can touch a Grand Seiko Spring Drive, which is accurate to within 2-3 seconds per year. In 2005, Seiko upped their game again: launching the world's first solar-powered analog watch that adjusts its accuracy by receiving radio signals from Japan, Germany, and the United States. Along with Citizen and Casio, Seiko created a dynamic center of global watchmaking that continues to make Swiss and German watchmakers look vaguely medieval.

Citizen and Casio compete with Seiko but mainly make excellent quartz watches. A costly Swiss mechanical watch might be accurate to within three or four seconds per day. A good quartz watch is accurate to within five seconds per year. Many now check with satellites to adjust for any error or daylight savings time. The newer ones have an invisible solar panel to recharge the battery. These watches run for 18 months in the dark and forever with a bit of light. They have a perpetual calendar that automatically adjusts for the length of the month until the year 2100.

Why 2100? Under the Gregorian calendar there are three rules governing leap years to keep calendars closely aligned with earth’s orbit around the sun.

Rule one is that a leap year is any year evenly divisible by four. This is the rule that people and watches both understand.

Rule two is an exception to rule one. It says that if a year is divisible by 100 it is not a leap year.

Rule three is an exception to rule two. If a year is evenly divisible by 400, it is a leap year. So 2000 was a leap year but 2100 will not be.

Watches with perpetual calendars, like most people, only understand the first rule. So on March 1, 2100 watches will think it is February 29. Manually advance the watch by one day (or wait for the satellite to do it) and it will be accurate for another century.

The Swatch Group

Nicolas Hayek was one of the few Swiss watch industry leaders who responded creatively to the quartz crisis. In 1983, he merged two distressed companies and launched dozens of whimsically designed, high-quality, low-cost, plastic-cased quartz watches. He thought these watches could be both a fashion statement and a mass-market product. Because he expected that they would be a customer’s second watch, he called his company Swatch. They were an instant success and a must-have fashion accessory in the 1980s-90s.

Swatch was so successful and the Swiss watch industry so devastated that Hayek was able to buy up many struggling watch brands. As a result, Swatch owns 18 brands and is now one of the world's largest watch companies (although by revenue still smaller than Rolex). The Swatch Group employs about 36,000 people in 50 countries. It sorts its brands into four tiers. Breguet, Blancpain, Glashütte Original, and Omega are the main top-tier brands. These companies design and build many of their components, including movements. The mid-tier brands, Longines, Rado, and Union Glashütte source movements from sister company ETA but sometimes develop in-house technology. Hamilton, Tissot, Mido, and Certina are entry-level watches that use ETA’s excellent movements, quality materials like sapphire crystal, and solid construction while staying reasonably affordable. Finally, Swatch, Flik Flak, and Calvin Klein make inexpensive "fashion watches.".

Glashütte Original

The German village of Glashütte in Saxony was born a watch town. In 1845, as Frédéric Chopin established himself in nearby Dresden, several famous local watchmakers moved to a small valley in the Ore Mountains to manufacture pocket watches. They chose this area for its proximity to Dresden's already established clockwork industry. Ferdinand Adolph Lange established A. Lange & Söhne, still one of the world’s most revered watchmakers. Moritz Grossman successfully petitioned the King of Saxony for a business loan and founded the German School of Watchmaking in 1878. The school operates to this day and helps account for the dense concentration of watchmaking talent in this part of Saxony.

Because horology is important militarily, the US bombed Glashütte (and shamefully firebombed nearby Dresden) at the end of World War II. The partition of Germany in 1949 meant that Glashütte became part of communist East Germany. With wartime reparations mandated by the Western Allies, the Soviet Union seized the surviving watchmaking machinery from Glashütte and forced seven independent watchmakers into one state-owned monopoly called GUB (Glashütte Uhrenbetrieb). Eventually, Russia realized that, as predicted by Marx’s labor theory of value, the tooling was useless without watchmakers, so they sent it all back.

Paradoxically, communism insulated Glashütte from the quartz crisis. Protected from capitalist market demands, GUB focused on traditional mechanical movements. After the reunification of Germany in 1989, the companies that made up the GUB registered as private businesses once again. The best known of these were A. Lange & Söhne, which joined Richemont and Glashütte Original, the remnant of GUB, which joined the Swatch group in 2000.

Omega

Louis Brandt founded Omega as La Generale Watch Co. in 1848. The company grew because of its innovative production control systems that featured interchangeable parts. It also grew because sailors needed reliable clocks.

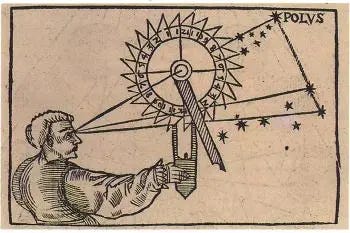

Early seafaring was treacherous. Tens of thousands of men died in shipwrecks not because they lacked maps, but because they could not determine where they were on the map. Before the development of reliable maritime clocks, sailors could use the stars to determine their latitude (north-south position) but could not reliably determine longitude, which requires an accurate clock. Unfortunately, sundials, hourglasses, water clocks, and pendulum clocks don’t work at sea. The critical need for reliable shipboard timekeeping led the British Board of Longitude Society to offer a large reward for the first accurate marine chronometer. Eventually, John Harrison won the prize.

But who certified the accuracy of marine chronometers? This job fell to national observatories, which certified any watch that passed its 60 day test for accuracy against astronomical reference clocks.

Omega celebrated its centennial in 1948 by producing its first automatic observatory-certified chronometer. Not anticipating much demand for a super-precise watch, Omega produced only 8,000 pieces. The watches were so well received that the company launched them as Omega Constellations in 1952. Throughout the 50s and 60s, Constellations were among Omega’s best-selling watches.

In 1957 Omega introduced a trilogy of tool watches that define the company to this day. They brought out the Seamaster diving watch favored by James Bond, the Speedmaster chronograph, which went to the moon with Apollo 11, and the Railmaster, a geeky engineering watch for railway workers, scientists, or anyone who worked near electrical fields. Seamasters and Speedmasters are incredibly popular. Railmasters, like Constellations, are geek watches. All are excellent.

Hamilton

Like many men of his era, my father wore one watch for his entire adult life. It was a Hamilton and I doubt he considered wearing anything else. Near the end of his life, the case back was worn so thin that it flexed like aluminum foil.

Before railroads, each town kept its own time and America recognized more than 144 official time zones as a result. The coming of railroad and telegraph lines meant that time needed to be consistent across towns, so accurate watches and standardized time zones suddenly mattered.

As railroads grew in importance, the Hamilton Watch Company was formed from three defunct watchmakers in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1892. At first, they made pocket watches for railroadmen. At one point most railroad conductors used Hamiltons, which made the watches popular with consumers. As aviation developed, Hamilton advertised wristwatches that kept coast-to-coast US Airmail running smoothly.

Unlike Swiss, German, Japanese, and Italian watchmakers, Hamilton went all-in against fascism during World War II. They shut down all consumer watch production and focused entirely on producing wristwatches, deck watches, and especially its sought after marine chronometers. Hamilton abandoned its dealer network – a critical asset.

After the war, Hamilton sought new ways to influence the public. It became known as “The Film Brand” because their watches appeared in more than 450 movies. In 1961, 26-year-old Elvis Presley wore a triangular Hamilton Ventura in Blue Hawaii. Bruce Willis wore a Jazzmaster in Die Hard in 1988. Oppenheimer featured a half dozen vintage Hamiltons because director Christopher Nolan is a big fan. Nolan built his movie Interstellar around the special Hamilton that astronaut Matthew McConaughey uses to communicate with his daughter Murphy played by Jessica Chastain. After Interstellar, Hamilton introduced The Murph – a clean, time-only dial with a cool story about a daughter keeping in touch with her father.

Longines

Longines was founded in 1832 by Auguste Agassiz, brother of Louis Agassiz, the famed biologist who discovered continental glaciation at Harvard. In 1889 Longines registered its winged hourglass logo, which remains the world’s oldest trademark still in active use.

In 1925, Longines produced the first dual-movement watch for pilots who crossed between time zones – the precursor to modern GMT watches. In 1931, Longines collaborated with Charles Lindbergh on the watch he wore when he became the first person to fly nonstop across the Atlantic. Today they are an excellent and underrated brand.

Richemont

Richemont owns some of the most esteemed and expensive brands in watchmaking, including Van Cleef & Arpels, A. Lange & Söhne, Montblanc, Baume & Mercier, Cartier, IWC Schaffhausen, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Officine Panerai, and Vacheron Constantin.

Cartier

Louis-François Cartier opened a jewelry shop in Paris as the city was torn apart by the 1848 revolution that gave us Les Miserables. By 1888, his son Alfred was making not only jewelry, but pocket watches for men and wristwatches for women. For his coronation in 1902, Great Britain’s Edward VII ordered 27 tiaras from Cartier, famously referring to the company as "the jeweler of kings and the king of jewelers".

Thanks to its heritage as a jeweler, Cartier has always focused heavily on the needs of women. As a result, Cartier has a larger watch business than Omega and is second only to Rolex among Swiss watchmakers.

Shortly after the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk in December 1903, Brazilian playboy aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont approached his friend Louis Cartier with a problem. Santos-Dumont liked to fly dirigibles around Paris but flying a blimp was a two-handed job, making pocket watches impractical. Could Cartier devise a solution?

Cartier designed one of the first known men’s wristwatches and the first pilot’s watch for Santos-Dumont. To make it more masculine at a time when only women wore wristwatches, Cartier crafted a unique square case and formal Roman numerals on the dial.

Panerai

Panerai is an Italian watchmaker founded in Florence by Giovanni Panerai in 1860, a year before the creation of a unified Italy. The company initially focused on military instruments such as timers, mine contact triggers, and submersible navigation tools.

When Italian frogmen needed dive watches in the 1930s, they turned to Panerai. Panerai turned to Rolex – then the world leader in waterproof watches. Panerai used Rolex Oyster cases and movements to create the Radiomir.

Radiomir was named after the radium-based luminescent paint they used for dial visibility in low-light conditions. Radium had recently been discovered in Paris by Marie and Pierre Curie. Unbeknownst to its early adopters however, radium kills. It killed Marie Curie who remains the only woman to win two Nobel Prizes. It also killed scores of "Radium Girls" who suffered fatal illnesses due to radium exposure while painting watch dials. The ability of American workers to sue companies for negligence grew out of the tragedy of these women who were sickened and killed after years of being told to “lip, dip, and paint” watch dials.

Panerai ceased watch production in the 1970s but in 1993 the company introduced Luminor watches with huge dials, oversized cases, and odd-looking crown locks that looked like something from another planet. Panerai had never sold to consumers and could not market the watch. Nobody bought them.

The company was saved by an unlikely combination of an internet mob, Sylvester Stallone, and Richemont. Legend has it that Stallone visited Panerai's Florence shop while filming Daylight in 1996 but it probably happened earlier. The actor became an enthusiast and ordered Panerais by the dozen. Panerai then developed a passionate online following in the very early days of the internet. Stallone and the Paneristi elevated Panerai's profile, which led to its acquisition by Richemont in 1997.

LVMH- Zenith

LVMH is a very large diversified luxury goods retailer. They own Louis Vuiton and Moet Hennesy (thus LVMH), Hublot, Tag Heuer, and their crown jewel, Zenith.

Zenith was founded by George Favre-Jacot, who dropped out of school at age nine to pursue an apprenticeship in watchmaking. He dropped out of his apprenticeship at age 13 to start his own company.

Like Omega, he really wanted to make watches in factories like Americans were doing. At the time, Swiss artisans made watch components in small, often home-based workshops and sent the parts to a master watchmaker for final fitting and assembly. But Favre-Jacout consolidated watchmakers under one roof in order to better control quality. Soon the company produced the world’s most accurate chronometers. They called one of their movements Zenith and soon named the company after it.

In 1969, as Seiko launched the world’s first quartz watch, Zenith introduced El Primero – the first integrated automatic chronograph movement. Today, El Primero remains the world’s most precise series-made caliber and is the only mechanical caliber that can measure time down to tenths of a second. It was a revolutionary movement that became an icon in the late twentieth century.

By 1972 however, Zenith was struggling badly. It had been bought twice and its new owners decided to abandon mechanical watchmaking altogether. They ordered the company to sell or destroy the plans and tooling for its mechanical calibers, including El Primero.

Fortunately an audacious watchmaker knew better. Charles Vermot built a secret room in the attic of the Zenith factory where he hid the tooling and documentation for El Primero. He then built a wall to completely conceal the room. Ten years later, Rolex suddenly realized the power of El Primero and decided to use it in their Daytona chronographs. This was astonishing – Rolex had never outsourced so much as a screw, much less an entire movement. At this point Vermot disclosed his secret room, which enabled Zenith to restart production and sell El Primero movements to Rolex from 1988 to 2000. This remains the only time Rolex has ever put a movement in their watch that they did not make themselves. Vermont’s courageous decision to protect El Primero helped Rolex – and it saved Zenith.

For a brand owned by the world’s most famous marketer of luxury goods, Zenith is oddly under-marketed. No celebrities wear it. No sports teams affiliate with it. You hardly ever see ads for it. But enthusiasts know that Zenith makes a terrific watch.

Independents and Microbrands

There are about three hundred independent watchmakers worldwide. Their watches sell for a between a few hundred dollars to a half million each for the latest Richard Mille monstrosity favored by celebrity athletes and gangsta rappers. Here are four that I know and like.

Breitling

Willy Breitling, took over the company his grandfather founded in 1932 when he was 19 and Europe was on the verge of war. He immediately added a reset pusher to Breitling chronographs, making them far more useful and winning the admiration of Britain's Royal Air Force. Today this design is basically universal.

Unfortunately for the RAF, the Nazis surrounded Switzerland and blocked exports of items like watches that could be used in the war effort. As a neutral nation, Switzerland took additional steps to block the export of any items that would threaten its neutrality.

But Willy was not neutral. He and a group of friends would drive to a field near the Breitling factory and set up a makeshift runway using their car headlights. They exported watches to the Royal Air Force by loading planes very quickly at night to avoid detection by local Swiss or Nazi intelligence officers.

To give himself a persuasive cover story during these midnight deliveries, Willy usually returned home via a local bar, where he would drink and make himself conspicuous. On more than one occasion, he spent the night in the local drunk tank, giving him an airtight alibi. But his courage ensured that Breitling watches and navigation instruments ended up in Allied hands.

Nomos Glashütte

Like all specialized industrial regions, the village of Glashütte spawns startups. One is Nomos Glashütte, founded in 1990 by Roland Schwertner, a computer scientist and photographer fond of minimalist Bauhaus aesthetics. Unlike other watchmakers in the village, which tend to be more refined, elaborate, expensive, high horology producers, Nomos watches are colorful, daring, and minimalist. You can often spot them from across a room. Nomos watches are wonderful and cost much less than many other German or Swiss luxury brands.

Christopher Ward

Christopher Ward is a microbrand that designs watches in England, makes them in Switzerland, and sell them via their website worldwide. It is the old Hans Wilsdorf formula. Their logo combines the English and Swiss flags. They make many different models, sizes, colors, and straps/bracelets. One or two of their models are technically innovative and all are excellent value.

Unlike Wilsdorf and Davis, Christopher Ward never changed its name. Not only does it sound like Montgomery Ward to an American, but Christopher Ward himself was a co-founder who deserted his colleagues and started a competing brand that failed immediately. I have argued with their CEO that they need to follow Wilsdorf and rename the company. (I suggested Aria, with models given operatic names like Bel Canto, which is already their best watch. Don’t hold your breath.)

Oris

Oris made my first Swiss watch and remains one of my favorite watchmakers. Founded in the little town of Hölstein in 1904, the company built clocks and pocket watches. When pilots demanded wristwatches, Oris soldered lugs onto their pocket watches. This worked well, since pilots could wind the huge pocket watch crowns while wearing gloves. In 1938, Oris launched Big Crown watches, which have been a signature watch ever since.

The quartz crisis very nearly killed Oris. In the early 1980s, they were down to a dozen employees. Finally, two Oris managers bought the business and made the brave decision to focus on selling mid-market mechanical watches. At a time when Swiss watches had retreated into luxury goods selling, it was not at all clear that there was a mid-market.

Oris has preserved a sense of humor rare in the staid world of Swiss watchmaking. Their mascot is a teddy bear; the rotor on many of their watches is bright red; and on a recent green watch Kermit the frog appears on the first day of each month. The company issues special edition watches that sponsor environmental groups to raise money for cleanups and limited editions to honor Louis Armstrong, Roberto Clemente, Carl Brashear, and Hank Aaron. It’s a great brand with some fine watches.

Conclusion

As digital devices became cheaper, tougher, more specialized, and more accurate, scientists, sailors, soldiers, divers, and pilots stopped relying on mechanical watches. But just as a music lover who spins vinyl often has a Spotify account, a watch lover with a well-crafted analog timepiece typically keeps a mobile phone handy.

Despite its fervent followers, the Swiss watch industry is in trouble. Exports of mechanical watches fell from more than twenty million units in 2014 to fewer than fourteen million in 2019 — a 30% decline in five years, according to Morgan Stanley. The post-Covid bubble in secondary mechanical watches has popped and used watch prices have fallen almost forty percent in the past two years, according to Watchcharts.

For perspective, Apple sold more than fifty million watches in 2022 — compared to about six million mechanical Swiss watches in recent years. (Morgan Stanley collects extensive Swiss data thanks to certification records and a strong industry association. Figuring out German, British, Japanese or American mechanical watchmaking is much more difficult).

Nonetheless, many people appreciate thoughtfully designed mechanical watches. The consulting firm Deloitte recently asked people in a dozen countries whether if given $5,000 they would prefer a luxury mechanical watch or the latest release of any smartwatch each year for five years. Between 55% and 75% of people in every country chose a mechanical watch. For now, at least, plenty of people value the artistry and craftsmanship of a tiny time machine.