The Seventy Percent Solution

70% Medicare For All is Better Than Shooting the Messenger

An alliterative assassin has forced our frustrating healthcare system back into public view. Booming sales of tasteless “Free Luigi Mangione” merch reflect a fondness for cold-blooded murder alongside our exasperation with health insurance. Not our finest moment.

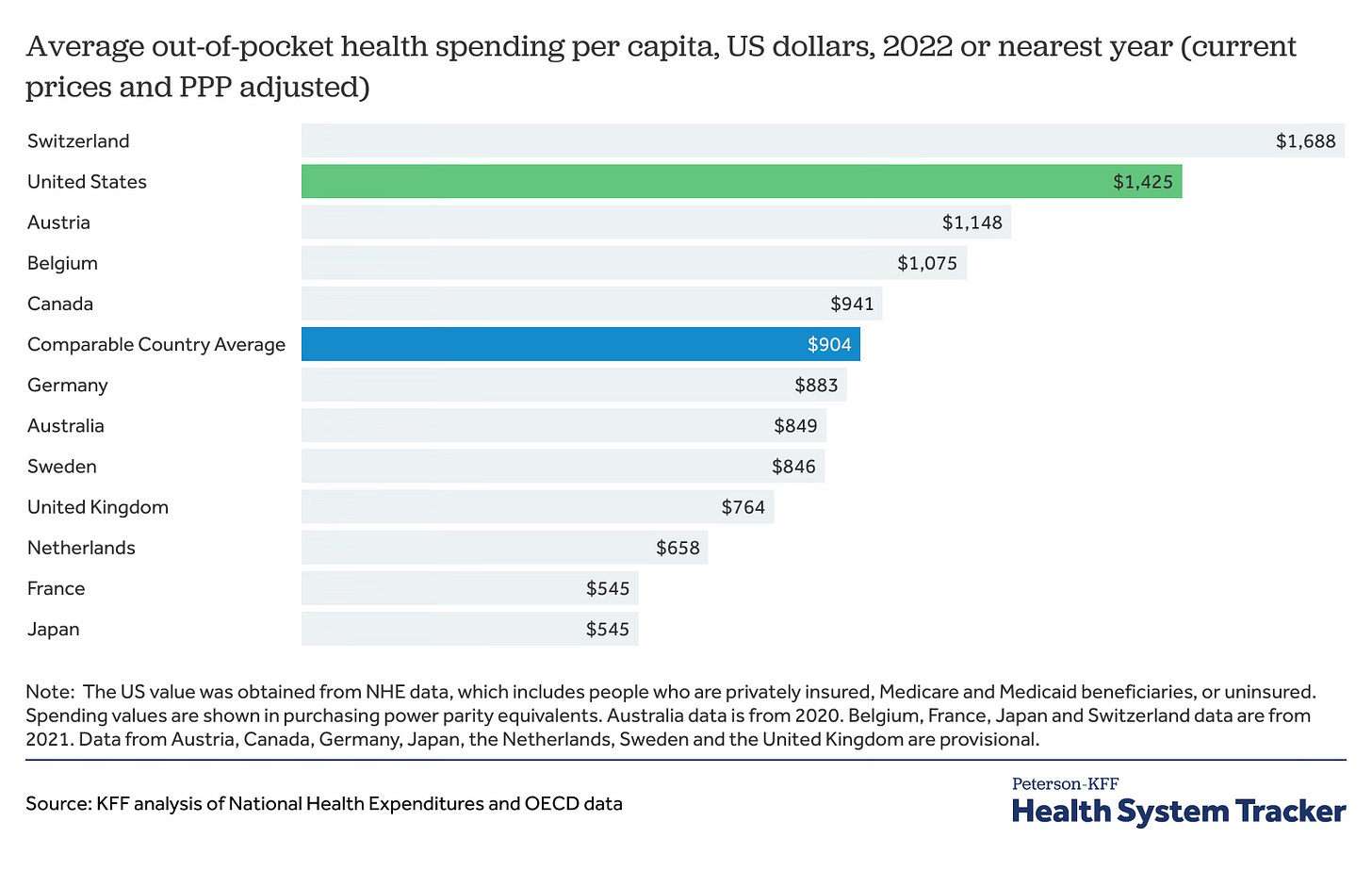

Sadly, we shot the messenger. Health insurance companies are not the core problem. Indeed, our insurance covers more out-of-pocket costs than the much-envied systems of Canada, Australia, Sweden, or Germany.

But we end up paying more because the bills are so damned high.

Hospitals, physicians, and drugs - not evil health insurance companies - have driven our costs higher. When the Kaiser Family Foundation compared the US with other developed countries, it concluded that most excess spending comes from providers, not payers. It found that Americans spend $12,197 annually on health care, compared to $6,514 in our peer countries.

Americans each spend $5,700 more per year than people in other affluent countries — and we get worse outcomes. This $5,700 tax falls especially hard on lower-income Americans. The 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation suggests that the total medical debt owed was at least $220 billion at the end of 2021.1 Many people with medical debt are financially vulnerable. From the indispensable Kaiser Family Foundation:

Where does this $5,700 of excess spending go? $4,500 goes to hospitals, drugs, doctors, nurses, and medical technology, while $680 goes to higher administrative spending. Each cost has a different dynamic, but hospital chains, physician groups, drug companies, and equipment makers earn vastly higher profits than the 2-3% returns that health insurers receive.

Unlike our peers, America has no national system that enables the government to bargain with providers. We have just started allowing this by having Medicare negotiate lower prices on a few drugs.

Government bargaining with providers is not a panacea. Many drug and equipment companies create products that reduce costs and save lives. Stifling their innovation is a terrible idea. However, these companies currently penalize Americans for our fragmented approach to bargaining. We effectively subsidize their global research and development because other countries bargain harder than we do. They punish Americans for our allergy to national purchasing programs. National bargaining for drug prices would force drug and equipment companies to spread their R&D costs further. We would stop subsidizing people in other countries.

Noah Smith described how Japan bargains with healthcare providers. Every citizen enrolls in an insurance program based on where they work or where they live. The government negotiates prices with providers and covers 70% of most services. Patients pay 30% (less for children, old people, and low-income families). Private insurance plans are available to cover all or most of the 30% cost-share. Despite having an older population, Japan spends far less of its GDP on health care than we do and, by most measures, gets better outcomes. Germany, Canada, Singapore, and Australia have similar programs. They lower prices by lowering provider costs with massive public bargaining power.

Why bother having private insurance at all? It surprises some people to learn that private insurers are a source of healthcare innovation, not just claims frustration. They are often skilled at leveraging technology, data, and partnerships. Private insurers pioneered outcomes-based payments, telemedicine, data analytics, wellness incentives, and on-site clinics for large employers. They are too fragmented to bargain prices with providers and drug companies — but they have a role.

70% Medicare for All is simple to understand in a complex policy world. It would create broad coverage, cost-sharing, and a role for private insurers. It would make cost containment feasible, so long as government negotiators overcome providers’ pricing power and bargain hardest where profits are highest: hospital chains, physician groups, and drug companies. They will and should accept higher profits in companies that invest more in R&D and take more risk.

It would also begin to move healthcare away from employment — the original sin in our health insurance system. And it would enable people with generous private insurance coverage to keep it (a huge stumbling block to Medicare for All).

A Seventy Percent Solution is not a single bullet. There are plenty of other critical reforms in health care, although they do not need to be addressed all at once. We should also:

Add dental, hearing, vision, and mental health coverage to Medicare.

Make Medicaid more like Medicare, although this is complicated.

Standardize Medicare Advantage and other private supplementary coverage to make different plans comparable.

Restrict drug patents, or the ability of pharma companies to “evergreen” them.

Address supply limits like pointless Certificates of Needs for hospitals, restrictions on training new physicians, or rules against immigrant physicians practicing here.

“Seventy Percent Medicare for All” is a lousy bumper sticker, but it is more fiscally realistic than what many Democrats wanted in 2016 and 2020. Public funds account for approximately 48% of total healthcare spending in the United States. But these funds are spent across many federal, state, and local programs, so none has the scale or statutory authority to bargain with providers. Outside of the military, we do not need government to deliver healthcare. But in a world where public funds already pay for a huge share of health care, it makes sense to create a public payer strong enough to ensure we get our money’s worth.

Assassinating an insurance company CEO is repugnant and does nothing to fix our broken healthcare system. Those frustrated by “Deny, Defend, Depose” should consider a seventy percent solution.

For comparison, Biden forgave $175 billion in student debt. Forgiving medical debt probably takes an act of Congress, but would be a vastly better use of public funds.

Marty,

A useful intervention, with good data, and this might be only kind of solution possible in this (benighted) country. But you forgot two big problems with the insurance company mode of financing health care: the incredible frustration of dealing with claims and payments (and denials) and the added bloat to an already monstrous financial system. DW