(Note: most of my posts are short. This one isn’t.)

As kid I was so skinny that my dad called me “Slim”. It didn’t last. By thirty I was gaining two or three pounds a year. As my belt got longer, I stayed strong and active and ignored the extra weight. By forty, I was no longer slim; by fifty, I was chubby. My body conceals my weight, which helped me conceal the problem.

At a physical exam in June of 2022, I stood six feet tall and weighed 290 pounds. It turns out that if you gain two or three pounds a year for forty years, you end up a hundred pounds overweight. Who knew?

We use a “body mass index” or BMI to measure obesity. BMI is calculated as your weight in kilograms divided by the square of your height in meters. A BMI of 18.5-25 is considered healthy; 25-30 is defined as “overweight”. Over 30 is obese. Over 40 is morbidly obese.

BMI is not a great measurement because it does not distinguish between a bodybuilder who is solid muscle from me, who is not. Despite this built-in composition error however, it remains a widely used heuristic because most people are not bodybuilders and would be healthier with a BMI under 25.

BMI is a crude measure, but so what? God takes the fat ones first — and I was fat. There are damned few ninety-year-old men with obesity. I was not just overweight. Staring at age seventy, I was teetering on morbidly obese.

I knew precisely how obesity would kill me. I was already insulin resistant; type two diabetes would follow. Obesity fuels inflammation and with it cancer, autoimmune disorders, cardiac stress, hypertension, and more. Obesity was already causing my hips and knees to wear down faster. It puts pressure on my kidneys and weakens my bladder muscles, increasing my risk of urinary stress incontinence. It made it harder to breathe at night. I had already been diagnosed with acute sleep apnea, which increases coronary stress. It takes a toll on mental health.

Globesity

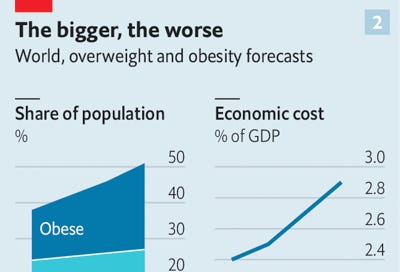

I was not alone. Obesity is now the world’s most common serious disease. It has tripled worldwide since 1975 and is now endemic in every advanced society and most developing ones. It affects three times more people than hunger does. The 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that 42% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over have obesity and another 31% are overweight. One-quarter of our children are obese. The World Obesity Federation projects that by 2035 half of the world’s population will be obese. Even some animals have grown dangerously fat.

This is completely new. In the early 1960s, fewer than 14 percent of Americans were obese. The disease is unrelenting: no country has ever reduced its obesity rates.

Researchers debate causes. Is endemic obesity the result of obesogens from plastic? Too much food? Limited access to healthy food? Sugar? Sedentary TV watching and computer use? Poor sleep habits? Too much dietary fat? Our gut biome? Social media? A virus? A political plot? I ruled out menopause.

The cause didn’t matter because my options were dismal. The standard treatment is a combination of diet, exercise, drugs, or bariatric surgery. Measured over five years, the first three rarely reduce body weight by five percent. Bariatric surgery produces excellent results but is invasive and irreversible.

Like any red-blooded American facing a serious health problem, I wanted a magic drug. As an incurable techno-optimist, I had been tracking a promising class of hormones used to treat diabetes that also caused weight loss.

Seriously? A magic shot for fat people? Big Pharma produces medical miracles, but…Big Pharma. My Republican father was a pharmacist who deeply distrusted drugs and drug companies. My primary care physician doesn’t like them much either. (I welcome this. A year earlier, I had asked him about Stanford research touting the benefits of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19. He politely dismissed the research as bogus – and he was right.)

However the trial data on a diabetes drug called terzepatide was impressive, so I summarized the research and sent it to my skeptical doc. He understood my dilemma, but once again advised against meds. He had solid clinical reasons for not prescribing. At the time, the FDA had not approved Mounjaro for obesity (it has now and Eli Lilly makes two identical drugs: Mounjaro for type two diabetes and Zepbound for obesity). The clinical weight loss trials were large, well-constructed, and delivered impressive results but, as he delicately put it, they were “run by the drug companies”. My rail-thin dad would have agreed.

As I investigated more deeply, however, I concluded that testing Mounjaro was less risky than remaining obese. And it was more reversible than surgery. I found a physician willing to prescribe the meds, secured a supply, and on August 8, 2022, administered my first injection.

Within six months, I lost more than a quarter of my body weight. I will not know for many years whether the weight loss will continue, whether it will endure, or whether unforeseen side effects will make me regret my decision to use the meds. But Jesus do I feel better.

This is a summary of what I learned about these drugs. It is one story and emphatically not data or medical advice. Your mileage will vary.

Diet, Exercise, and Drugs

I eat mostly healthy food, but am not good at portion control. I eat big servings, snack, and help myself to seconds. Bread is for soaking up leftover oil, right?

I would be happy to just eat less. But if cutting calories worked reliably, obesity would be rare. Two-thirds of Americans regularly attempt to eat fewer or healthier calories. Although many diets produce real weight loss for a year or two, most people regain their lost weight within five years. In 2011, I lost 35 pounds adhering to a Pritikin low-fat, no refined carbs, regular exercise regime. The weight came back, but I don’t blame Pritikin for that. Evolution has trained our bodies to defend against weight loss even if our weight level is unhealthy.

Also, losing weight and regaining most of it is not a complete failure. Several studies find that those who regain most but not all of the lost weight still enjoy a significant reduction in the risk of progressing to type two diabetes. Most research finds that even modest weight loss is valuable – but these same studies also conclude that greater and more sustained weight loss provides even larger benefits.

What about exercise? Working out is essential to health but rarely sufficient to achieve sustained weight loss. I walk a couple of miles and bicycle most days. I hike and swim and see a demanding strength and flexibility trainer for an hour twice each week. Exercise helps curb my appetite. It is essential for my mental and physical health. But a pound is 3,500 calories, which translates to between three and ten hours on a treadmill. You lose weight in the kitchen, not the gym – even if the gym helps.

Which leaves drugs, which have a terrible record. Like diets, they struggle to exceed a safe and sustainable loss of body weight greater than five percent over five years. Worse, these drugs have produced horrible side effects so often that I presume them guilty until proven innocent.

In 1934, tens of thousands of Americans were using dinitrophenol to lose weight. It turned out to cause cataracts and even death. By one estimate 25,000 people were blinded by the drug, but people still buy it online.

During the 1970s amphetamines (speed) were popular for weight loss, until the risk of addiction and other side-effects became obvious.

In 1977, 70,000 people took Ephedra, an herbal medication, before it too was shown to be lethal and banned.

In the 1990s, the FDA approved fen-phen after a single small study of 121 people. Approval unleashed millions of prescriptions, some leading to serious heart valve lesions that resulted in the withdrawal of the drug in 1995.

The drug Acomplia (rimonabant) looked encouraging in randomized trials. However, a subsequent trial of nearly 19,000 participants in 42 countries found a significant excess of depression, neuropsychiatric side effects, and suicidal ideation.

The FDA and EU regulators withdrew approval of Meridia (sibutramine) over safety concerns that emerged after these meds were given the green light.

Weight Loss Surgery

The most effective treatment for obesity by far is bariatric surgery, which reduces the size of the stomach. This procedure has been transformed from lap-band to sleeve-based and now has far fewer complications than a decade ago. It's often done as a laparoscopic surgery, with small incisions in the abdomen. A surgeon reduces the size of your upper stomach to a small pouch about the size of an egg by stapling off the upper section of the stomach.

Bariatric surgery is often transformative. It reliably reduces body weight by about one-quarter and offers significant long-term health benefits. Compared to obese adults who don’t get the surgery, bariatric patients live longer, have less high blood pressure, enjoy an 83% lower risk of developing diabetes, a 78% chance of reversing established diabetes (with some relapses), a 29% lower risk of having a heart attack, a 44% lower risk of developing cancer and dying of it, and an astonishing 29% lower overall mortality. Very few medical interventions demonstrate results like this.

Nonetheless, fewer than one in 400 American adults with obesity undergo bariatric surgery each year. It appears to be one of the few medical interventions that are massively under-utilized, perhaps because it is irreversible and seems invasive. Irrationally perhaps, I wished to avoid it – which meant that my therapeutic options were not great.

As I researched obesity, I came to realize that many healthcare providers hold a deeply distorted view of the disease. Our leading economic, cultural, and medical institutions still view obesity as a problem of personal responsibility instead of a complex, chronic disease with many subtypes like cancer. Physicians who would never allow heart disease to go untreated take a much more relaxed view of obesity – perhaps because they know that almost everyone would benefit from fewer, healthier calories and more exercise. Industrial-scale promotion of large servings of unhealthy food does not help – but neither do physicians who shrug off the disease as a common and intractable personal failing.

Congress made things worse by declaring obesity a cosmetic issue, not a metabolic one. The 2003 Medicare Modernization Act bars Medicare from paying for drugs “used for anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain” even though the American Medical Association recognized obesity as a disease in June 2013 and Medicare covers the cost of bariatric surgery to treat obesity. Because almost all private health insurance copies the Medicare drug formulary, very few health insurance policies cover anti-obesity drugs.

Using Fake Hormones to Hack Your Endocrine System

Hormones are powerful chemical messengers created and released by our endocrine system. They control almost every process in our body, including metabolism, growth, emotions, sexual function, and sleep. In the early twentieth century, researchers discovered that the human intestine releases hormones in response to food. These incretin hormones are small proteins (peptides) that stimulate the pancreas to secrete insulin (a second hormone) and glucagon (a third hormone), which regulate appetite and blood glucose levels. These hormones regulate the level of glucose in the blood and could therefore treat type 2 diabetes.

Many people with diabetes do not secrete enough GLP-1. Unfortunately, you cannot just give people GLP-1 because it breaks down immediately. So scientists began to search for GLP-1 mimetics or agonists (i.e., imitators). They were assisted in this quest by the discovery that Gila monster venom is a natural incretin mimetic that helps regulate blood sugar.

In the early 1990s a young Danish scientist named Lotte Bjerre Knudsen working at Novo Nordisk developed a slightly maniacal view of the potential of GLP-1 medications to treat both diabetes and obesity. She spent years screening tens of thousand of chemical compounds to find one that could bind to the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor sufficiently to stimulate insulin secretion. This effort was controversial and more than once Novo Nordisk threatened to shut the effort down. Knudsen not only persisted, but her team eventually developed a new compound called liraglutide, which uses a fatty acid to dissolve in water and bind to albumin, an essential protein made by the liver and the most abundant protein in blood.

Knuden’s discovery of ways to make GLP-1 hormones bioavailable was worth tens of billions of dollars. It transformed Novo Nordisk into Europe’s largest company and has in recent years accounted for virtually all Danish economic growth. In America, Knudsen would have become rich on her discovery. In Denmark, she told one interviewer, “I don’t care that much about money, I’m a socialist! I have never asked for a raise in 34 years.”

Soon these incretin agonists became an important class of therapeutic agents in treating type 2 diabetes. Researchers have long known however, that GLP-1 is doing more than regulating insulin levels. It slows down the rate of “gastric emptying”, so food stays in the stomach longer and suppresses feelings of hunger. It affects the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that controls hunger, and may interfere with dopamine production – the feel-good hormone that rewards eating. It appears to have a direct effect on fat, making the body more likely to break it down.

People with diabetes who took GLP-1 agonists to control their blood sugar lost a lot of weight. The drug companies formulated stronger, longer-lasting versions of the drug targeted at obesity. Two of the most promising incretin agonists are semaglutide, which Novo Nordisk marketed as Ozempic for diabetes and Wegovy for weight loss and tirzepatide, which Eli Lilly markets as Mounjaro for diabetes and Zepbound for weight loss. (Why give the same drug two names? Lots of reasons, but a big one is that doctors will prescribe diabetes meds off-label for obesity because these drugs are covered by insurance, which will not cover the same drug for weight loss).

Since Knudsen’s breakthrough, drugs based on incretin agonists have made steady progress for almost two decades. They typically start as daily injections, are reformulated as weekly injections, and then come out as pills. They start out treating type 2 diabetes and then receive approval (or are prescribed off-label) to treat obesity – sometimes under a different dosage or brand name. The FDA has steadily approved variations of these drugs for almost twenty years.

2005: Eli Lilly’s Byetta (daily injected exenatide) for diabetes.

2010: Novo Nordisk’s Victoza (daily injected liraglutide) for diabetes.

2014: Novo Nordisk’s Saxenda (daily injected liraglutide) for weight loss.

2017: Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic (weekly injected semaglutide) for diabetes.

2019: Novo Nordisk’s Rybelsus (daily oral semaglutide) for diabetes.

2021: Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy (weekly injected semaglutide) for obesity. The relevant trial, published in the NEJM in March 2021, was a double-blind test of 1,961 adults with a body-mass index of 27 or higher who did not have diabetes. Enrollees were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to 68 weeks of treatment with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide (at a dose of 2.4 mg) or placebo, plus diet and lifestyle intervention. The mean change in body weight from baseline to week 68 was −14.9% in the semaglutide group as compared with −2.4% with placebo, for an estimated treatment effect of −12.4% of body weight.

2021: Novo Nordisk initiated a 68-week phase 3a trial for an oral semaglutide to treat obesity and is expected to seek regulatory approval. No brand name has been announced.

2022: Novo Nordisk completed a phase 1b trial pairing semaglutide with the amylin analog cagrilintide. Over 20 weeks, the addition of cagrilintide nearly doubled the rate of weight loss caused by semaglutide alone. As of 2024, phase 3 trials are ongoing.

2022: Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro (weekly injected tirzepatide) for diabetes. Tirzepatide combines a GLP-1 receptor agonist similar to semaglutide with a second incretin hormone called GIP, for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, to form a single novel molecule. Clinical trials suggest that combining the two hormones resulted in significantly greater effects on glucose and body weight than a GLP-1 agonist alone.

In early 2022, Eli Lilly announced the stunning results of its phase 3 trial of Mounjaro for obesity. This was a controlled, double-blind, global registration trial that enrolled 2,539 participants to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in adults with obesity but without diabetes. Participants in the highest dose (15 mg) group lost an average of 22.5% of their body weight, comparable to bariatric surgery. Sixty-three percent of those in the 15 mg group achieved at least 20% body weight reductions compared to 1.3% of those taking a placebo. As with Wegovy trials, all participants received diet counseling and were urged to reduce food intake by 500 calories/day.

These results went through extensive peer review, but initial results blew endocrinologists away and made headlines around the world. Mounjaro’s results were better even than Wegovy's and caught my attention. (Last November, more than a year after I began taking it, the FDA approved the use of tirzepatide for obesity.)

Mounjaro

Once tirzepatide was available as Mounjaro for diabetes, I wanted to know more about its side effects. Incretin hormone agonists have never been risk-free medications. Fortunately, serious side effects are rare and the most common side effects are transient and not especially serious — although they are severe enough that about 15% of participants elected to stop participating in the Phase 3 trial. (Then again, so did 25% of those receiving the placebo!)

Like Wegovy or Ozempic, Mounjaro is a titrated medication – you steadily increase the dosage. In trials, most side effects occurred when users moved to a higher dosage. The most commonly reported adverse events were GI-related, generally mild to moderate in severity, and usually occurring during the dose escalation period. For those treated with 15 mg of Mounjaro (the highest tested dose), 23% experienced nausea compared with 2% in the control group. For diarrhea, the treatment/control was 22%/2%. For vomiting, it was 9%/2%. This is similar to the side effects of Wegovy.

Some documented risks of semaglutide injections do not appear in the Step 1 trial. The FDA cites an increased risk of Thyroid cancer (thyroid C-cell tumors) based on rodent studies but no research to date has documented an increase in human populations, diabetic or otherwise. Importantly, however, it is still early days, so many risks may not yet have revealed themselves (for example, hair loss is widely cited among thousands of Wegovy user reviews here, here, and here but never mentioned in the trials literature).

There is also some evidence that as much as 40% of the weight lost is muscle, bone, and other lean tissue mass, not fat. Although there are few clinical reports of sarcopenia, anyone on these meds needs to do regular resistance training because losing muscle mass is potentially quite serious.

Because Mounjaro produced more significant weight loss with side effects that were no worse (and because, unlike Wegovy, it had not yet suffered supply disruptions), I investigated it more carefully. The decision came down to either dieting to lose 20-30 pounds, probably temporarily, or seeing if injecting faux incretin hormones might improve my portion control and enable greater, more sustained weight loss. Doing nothing seemed unacceptably risky to me.

My GP said he would not prescribe Mounjaro, although he acknowledged that my case for testing the meds was strong. So I found a physician with experience using incretin hormone agonists (mainly semaglutide) who agreed to prescribe Mounjaro. He was not nervous about prescribing it for obesity when the FDA had only approved it for type 2 diabetes in part because about 40% of drug prescriptions are now “off-label” (an approved drug prescribed for a non-approved use) and he had been prescribing Ozempic (a type two diabetes med) for obesity for several years.

The pen injectors are easy to use. It takes ten seconds to remove the cap, unlock the pen, place it against my thigh, and press a button. A short, invisible needle descends, injects, and retracts. It does not hurt and rarely bleeds or produces a sore spot. I toss the empty pen into a sharps container. Needles don’t bother me, but with pens, you never see the needle.

Mounjaro pens come in boxes of four and are sold in six strengths: 2.5 mg, 5.0 mg, 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 12.5 mg, and 15 mg. You progress to the next level after you finish a box of four weekly injections. My doc advised skipping the 2.5 mg, which has little clinical effect and is mainly used to get your body used to the meds.

The drugs affected me immediately. I was instantly less hungry and found it easy to eat much less. Surprisingly, I immediately lost interest in both alcohol and coffee. I used to drink 3-4 glasses of wine per week and have a double espresso in the morning. I found myself saving half of my dinner for the next day’s lunch. My diet has not changed a lot, aside from the amount I eat.

Side effects have been noticeable but they have diminished over time. I had an hour of nausea (queasiness like car sickness; no vomiting) after my first 5 mg shot of Mounjaro but experienced fewer side effects when I moved to 7.5mg. When I started on 10mg, I got the occasional day of moderate GI symptoms (upset stomach, vile burping, mild diarrhea). I used Pepto Bismol tablets to calm it down. For two weeks, I had these symptoms for a few hours a couple of days each week. It was unpleasant but not debilitating; I felt uncomfortable, not sick. I have use the maximum (15mg per week) dose of Mounjaro for over a year and experience occasional, temporary side effects – mostly very odd burping.

Using Mounjaro is nothing like dieting. I eat as much as I want – but I want to eat much less. I limit my portions not because of my steely resolve, but because I am not all that hungry. Water often curbs what little appetite I have. I completely understand why Elon Musk and the “must stay thin” crowd in Hollywood are demanding these drugs. For me, Mounjaro has been easy and kind of magical.

When I began treatment on August 8, 2022, I weighed 282 pounds – down a bit from my June physical. As of July, my weight has fallen from 290 to 215 lbs, my LDL cholesterol from 78 to 41, my fasting glucose from 128 mg/dl (pre-diabetic) to 114 (fine), and my blood pressure from 129/85 to 108/74. I work out much harder, bike and walk faster, creak less, stretch more easily, and no longer suffer edema. Better yet, since I began using the meds, they have been associated with a broad anti-inflammatory affect that reduces all sorts of bad outcomes, including kidney disease, cancer, Alzheimers, and severe Covid.

My rate of weight loss has declined over time. At first, I lost four pounds per week. Soon it was three. Then two. I weighed myself most days, cursed the inevitable variation, and recorded my weight when I injected each week.

How much weight should I lose? Establishing a fact-based target is fraught. BMI tables suggest that losing one hundred pounds or more would be fine. I remained clinically obese until I weighed less than 220 pounds; I will be overweight until I weigh less than 180 lbs. The National Center for Biotechnology Information confirms that all-cause mortality is lowest with a BMI of 20-25, bodybuilders excepted. Formulas used by the US Navy based on the ratio of height/waist size yield similar recommendations. I have only modest confidence in either the appropriateness of these targets or my ability to hit them even with meds. For now, less weight is healthier.

The Economics of Obesity

Obesity is a byproduct of human flourishing. Most people have more than enough to eat and do not need to undertake constant, grueling physical labor. This is an obvious sign of progress. But with it has come real human and economic costs. Obesity sickens and kills millions and imposes a cruel stigma on its victims. It is also expensive. Estimates by the McKinsey Global Institute place the worldwide cost of obesity at about $2 trillion a year – about equal to the cost of smoking or armed violence including war and terrorism.

The treatment costs less than the disease, but Mounjaro and Wegovy are nonetheless quite expensive. A box of four weekly Mounaro injections costs $1,000, or $13,000 per year. Moreover, the expense is life-long: patients typically regain their lost weight if they discontinue the meds. Most private health insurance plans do not include them in their formulary of approved medications. They are unlikely to do so as long as Medicare is barred by statute from paying for anti-obesity medications. To date, no online Canadian pharmacy sells Mounjaro. When Japanese pharmacies obtained the meds, they were overwhelmed by foreign demand and quickly banned exports.

If 140 million Americans need expensive meds to treat a damaging medical condition, that’s a massive market. Investors have worked out that anti-obesity drugs will be in the top dozen of all drugs by global spending. Mounjaro-maker Eli Lilly’s stock now trades at double industry multiples. This may be because Congress is already looking at legislation to increase access to these drugs (and increase drug company revenues. The two go together.)

In 2023, The Economist reported:

Excitement about the drug has kept Novo Nordisk in the headlines. Its market value has nearly quadrupled in the past five years. Earlier this month it reached $444bn, handbagging LVMH, a purveyor of luxury goods, off its perch as Europe’s most valuable company. Novo Nordisk’s main rival, Eli Lilly, which has a similar drug called Mounjaro (tirzepatide), is worth $522bn, more than four times what it was at the start of 2019.

It isn’t just investors who are jubilant. Not long ago Morgan Stanley, a bank, estimated that global sales of such weight- management drugs could reach $54bn annually by 2030. Now it puts the figure at $77bn. By comparison, last year they raked in just $2.4bn. The potential bonanza is attracting imitators. These include big pharma (for instance, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer), not-so-big pharma (Jiangsu Hengrui, Structure Therapeutics), and biotech startups (Carmot Therapeutics in California, Gmax Biopharm and Sciwind Biosciences in Hangzhou).

At scale, the cost of using expensive meds to treat obesity is far cheaper than the cost of not treating it. The political question of who pays will turn in part on whether we see obesity as a social disease like cancer or a matter of personal responsibility like opioid abuse. (These are not useful clinical distinctions, but they often drive healthcare politics.)

Conclusion

Don’t get fat. Injecting imitation hormones every week to defeat obesity is a desperate move. You and I would both prefer better choices.

If you find yourself medically (not culturally) overweight or obese, get help. Learn from the appended resources. Keep track of the treatments, which are evolving quickly. I have no idea if these therapies will work long-term for you, me, or anyone else – but trial data and my experience to date suggest that incretin hormone therapy is very promising. With luck and funding, they may soon improve and extend the lives of billions of people who suffer from obesity worldwide.

Updated June 2024

Resources

Alexander, Scott. “Semaglutidonomics.” Substack newsletter. Astral Codex Ten (blog), November 23, 2022. Semaglutidonomics - by Scott Alexander - Astral Codex Ten.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition “Long-Term Weight-Loss Maintenance: A Meta-Analysis of US Studies.” https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/74/5/579/4737391

Cawley, John, Adam Biener, Chad Meyerhoefer, Yuchen Ding, Tracy Zvenyach, B. Gabriel Smolarz, and Abhilasha Ramasamy. “Direct Medical Costs of Obesity in the United States and the Most Populous States.” Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 27, no. 3 (March 2021): 354–66. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2021.20410.

De Block, Christophe, Clifford Bailey, Carol Wysham, Andrea Hemmingway, Sheryl Elaine Allen, and Jennifer Peleshok. “Tirzepatide for the Treatment of Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: An Endocrine Perspective.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 25, no. 1 (2023): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14831.

The Economist. “A New Class Of Drugs For Weight Loss Could End Obesity,” March 12, 2023. A new class of drugs for weight loss could end obesity | The Economist

Financial Times. “Big Pharma Targets $50bn Obesity Drugs Market as Demand Booms,” November 21, 2022. Big Pharma targets $50bn obesity drugs market as demand booms

McKinsey Global Institute “How the World Could Better Fight Obesity” How the world could better fight obesity | McKinsey.

Morgan Stanley Research: “Unlocking the Obesity Challenge: a >$50bn Market” Unlocking the Obesity Challenge: a >$50bn Market

New England Journal of Medicine “Long-Term Persistence of Hormonal Adaptations to Weight Loss” https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1105816.

Thompson, Derek: Plain English podcast “How Weight-Loss Drugs Could Impact U.S. Healthcare and Food. Plus, the Biggest Problems With GLP1s”. https://www.podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/how-weight-loss-drugs-could-impact-u-s-healthcare-and/id1594471023

Topol, Eric. “The New Obesity Breakthrough Drugs.” Substack newsletter. Ground Truths (blog), December 10, 2022. The New Obesity Breakthrough Drugs - by Eric Topol

Vadher, Karan, Hiren Patel, Reema Mody, Joshua A. Levine, Meredith Hoog, Alice YY. Cheng, Kevin M. Pantalone, and Hélène Sapin. “Efficacy of Tirzepatide 5, 10 and 15 Mg versus Semaglutide 2 Mg in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Adjusted Indirect Treatment Comparison.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 24, no. 9 (2022): 1861–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14775.

Well written, Marty. As neighbors, I’ve watched you melt before my eyes. With you as inspiration, I began my Mounjaro/Zepbound/Tirzipetide journey. I was 66/6’-2”/258. After 9 months, im down to 208-a loss of 50 pounds. My old closets hang baggy on me and I’m thrilled to buy new ones. I can’t use any of my old belts. I walk the golf course and have more energy. I started using off brand Tirzepitde at $280/ month instead of $1,100. I had an exchange with them yesterday asking about how much notice might the FDA give before rescinding the exception allowing compounding pharmacies to produce and sell it since Eli Lilly can’t meet demand. They responded “a few eeeks”. They are concerned about a cease and desist order. They did say that the medicine will stay good for up to 12 months in the fridge. I’m going to buy 9 months supply. The pharmacy I’m using is called Slimdownrx. I’ve done two injections at 15ml and don’t notice any difference. I love saving the $800 a month. Oh, Marty! You must buy some new 34/32 Levi’s-the size you last wore in 1975!

Thanks for your wonderful post which perfectly balances the scientific, social, economic, and personal dimensions of our classic first world problem.

I was so inspired by your journey when we discussed it last year that I recently jumped on the bandwagon!