Mobster Wanted. Skip the Details.

How Zero-Sum Leaders Take Over a Positive-Sum World

Our ancestors lived in constant crisis. When they had a choice, they followed leaders with courage, conviction, and clarity, even when these leaders were dead wrong.

This was rational. A clear direction meant possible success in situations where indecisiveness meant certain failure. The more desperate the need, the more likely humans are to support a decisive leader.

In other words, we are hard wired to confuse confidence with competence. Bill Clinton understood this. He used to say, “Strong and wrong beats weak and right.” He knew that hesitant or uncertain leaders lose credibility even when their views are correct.

Labor leaders know this well, especially if their members are blue-collar men. They often present themselves as tough, even menacing because workers whose backs are to the wall prefer a determined fighter over a clever explainer.

During the sixties, the Teamsters were America’s largest and fiercest union. Its president, Jimmy Hoffa, was convicted of jury tampering, attempted bribery, conspiracy, and mail and wire fraud. Complaints that Hoffa was a sociopathic criminal missed the point. His supporters responded: “He may be a mean little crook. But he is our mean little crook.” Harvard-educated Bobby Kennedy failed to understand this in prosecuting Jimmy Hoffa in the 1950s and most college-educated Democrats do not understand this about Donald Trump today.

Donald Trump loves mobster cosplay. He likens himself to Al Capone and plays the transgressive outsider who thrives by breaking rules. The New York Times described him as leaning into an “outlaw image.” This (to say nothing of a string of felony convictions) is an odd look for a man about to swear to uphold our Constitution.

Trump’s persona is not just theatrics. His upbringing and business dealings were deeply connected to the mob. His mentor, Roy Cohn, was a lawyer for the Gambino crime family. In Cohn’s living room, Trump met with “Fat Tony” Salerno, boss of the Genovese family, to arrange the concrete for Trump Plaza. Although many construction executives found it necessary to deal with the mafia in mid-20th century New York, the experience shaped Trump’s worldview. Everything is a racket, and only insiders win.

Like a toughened union leader, Trump is able to appeal to people who feel betrayed by by a failed promise of equality and fairness. Anyone who has organized blue collar unions recognizes his offer of inclusion, power, and security.

In Trump’s worldview, society isn’t a collaborative meritocracy where everyone gets a fair shot; it’s a ruthless battleground where survival hinges on cunning and strength. This is a sharp departure from traditional conservatism, which at least paid lip service to the rule of law and fair competition. Trump dismisses such ideals as manipulative tools wielded by elites to maintain control. Instead, he offers his followers a stark narrative: he will help them prevail in a world ruled by self-serving exploiters. It’s no coincidence that in 2020, Trump attracted Bernie Sanders supporters after Democrats coalesced around Biden.

Like Sanders, Trump appeals to those disillusioned by democracy’s unfulfilled promises of opportunity and justice. However, unlike Sanders, Trump replaces the reformist ideals with a transactional vision rooted in loyalty and power. He speaks directly to those who see life as a fight for survival, arguing that fairness is a luxury for the naive. The President of the Teamsters Union recognized this sentiment’s resonance enough that he addressed Trump’s convention and withheld an endorsement of Kamala Harris.

Trump’s mindset is proudly zero-sum. A recent Harvard University study reveals that zero-sum thinking has become more common on both the left and the right. People across the political spectrum, including affirmative action advocates and anti-immigration nativists, believe that gains for one group mean losses for another. This zero-sum mindset extends to trade, wealth distribution, and economic success. It cuts across traditional political divides.

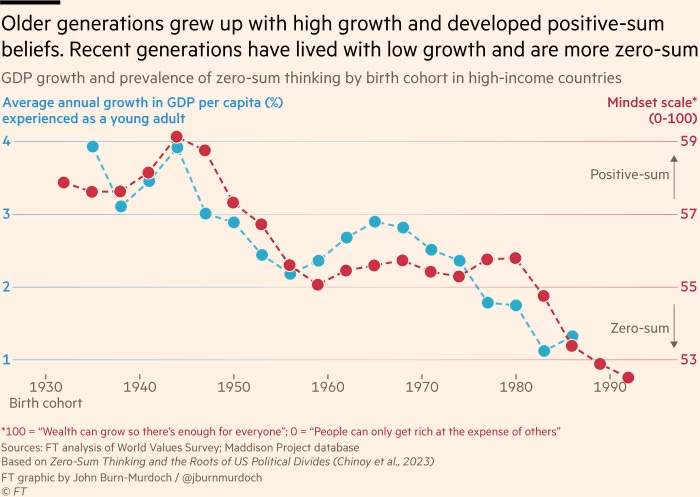

The study found that economic mobility shapes how zero-sum your attitudes are. If you grow up, as I did, amidst the abundance and growth of the postwar era, you are more likely to adopt a positive-sum mindset. You are likely to believe that the pie can grow for everyone. In contrast, if you grew up with fewer prospects for upward mobility, you are more likely to see success as a finite resource and conclude that hard work offers little reward. These beliefs are rational reflections of different lived experiences. I will advance the case for positive-sum thinking on practical grounds, not because one view is inherently more moral than the other.

Countries can adopt zero-sum thinking. As the excellent John Burn-Murdoch at the FT reports, “Every five to 10 years, the World Values Survey asks people in dozens of countries where they would place themselves on a scale from the zero-sum belief that “people can only get rich at the expense of others,” to the positive-sum view that “wealth can grow so there’s enough for everyone.”

Results show that people in high-income countries have become 20% more zero-sum over the last century, particularly during economic slowdowns like the 1970s and the previous two decades. This shift correlates with slower income growth and rising beliefs in luck over effort as the key to success.

When rising economic tides lifted all boats the average worker’s material life improved, even if some boats leaked and others became yachts. Rapidly growing economies produced more positive-sum thinkers who also cared about addressing economic fairness and equality. On the other hand, self-identified Democrats who voted for Trump in 2016 scored very high on zero-sum beliefs.

Zero-sum thinking can fuel a vicious cycle. Economic stagnation breeds defensive thinking, stifling innovation and growth. It fosters populism, conspiracy theories, nativism, and distrust of cooperation. Voters turn to decisive leaders, even/especially if they are mean bastards. Zero-sum mindsets can go viral.

Some prominent progressives argue that “economics are not zero-sum, but political power is.” If one group wins power, another must lose. This reflects a very old debate in political science that Thomas Hobbes kicked off with the Leviathan in 1651. Most modern scholars conclude that in cooperative systems like democracies or trade networks, power can be positive sum, whereas in competitive or anarchic environments like international relations or resource struggles, power is more likely to be negative or zero sum. As always, political outcomes depend on institutions, governance structures, and human behavior — but power is not always zero-sum.

In politics and economics, zero-sum thinking discourages trust and cooperation among liberals and conservatives alike. Solidarity is impossible if those around you are rivals or threats, not collaborators. Global politics is increasingly a contest between those who value the positive-sum growth of communities and economies and those whose negative sum worldview supports the mobster’s infantile creed: I want mine.

Pushing back on zero-sum thinking requires a combination of political courage and toughness. It means challenging our broad retreat from globalization, except as required for national security. It means emphasizing growth and abundance, not just redistribution. It requires patriotism that reinforces a positive-sum view of communities and human connection. Our country and communities are much more than the sum of the individuals who contribute to them. At our best, Americans know this.