I have a weakness for mechanical sports watches. Those who dismiss my pastime as pretentious are missing a bigger problem. My intense, longstanding, and time-consuming interest in tiny time machines verges on OCD. I’d happily settle for pretense.

My neurosis has produced an embarrassing symptom: I love Rolex. Mostly. Rolex dominates mechanical watchmaking thanks to three complementary strengths: It is technically innovative, it has built world-class (largely secret) manufacturing capabilities, and it is a marketing genius. Only one other watchmaker in the world shares these strengths: Apple. Today, let’s look at the remarkable similarities between Rolex and Apple. In explaining what I admire, I will also describe what I genuinely dislike about both companies.

Innovations

At the turn of the twentieth century, clocks were shrinking. Large clocks in the town square had long given way to grandfather clocks and tambours with drum-shaped cases that chimed the hour from middle-class mantels. Prosperous men carried pocket watches. Some women wore “wristlets” to tell time, although these small watches were famously inaccurate.

Born 144 years ago today, Hans Wilsdorf was a Bavarian orphan who moved to London and began importing Swiss timepieces. One of his suppliers, the Aegler company of Bienne, specialized in manufacturing small, precise movements. While still in his twenties, Wilsdorf developed a powerful conviction: watches would keep getting smaller and would become must-have devices and fashion goods as clocks moved from homes to pockets to wrists. A century later, Steve Jobs had the same idea about computers.

Wilsdorf saw three barriers to the mass adoption of wristwatches. They were less accurate than pocket watches. They were more exposed to moisture and dirt, which could ruin them. And they needed constant winding, an easier and more fidget-soothing task on a pocket watch. Fortunately, Wilsdorf was obsessive and determined to conquer all three problems.

But first, he needed a short name for his company that was easy to pronounce in any language, memorable, and friendly. In 1908, he settled on Rolex. Sixty-eight years later, Steve Jobs named his company Apple for similar reasons.1

Accurate. In 1914, Wilsdorf took a step considered preposterous at the time – he submitted one of his Aegler-powered watches to the Kew observatory in the United Kingdom. Kew conducted the world’s most stringent chronometric accuracy tests. They subjected marine chronometers to tests that lasted 44 days because, before GPS, marine navigation required accurate timekeeping. Chronometers certified by Kew assured the safety of the thousands of sailors that kept the British Navy ruling the waves.

The Rolex performed exceptionally well on chronometric tests and received the "A" certificate from Kew. Thus, Rolex became the world's first wristwatch to be certified as an observatory-grade chronometer. As a result, Rolex operated on a completely different level than traditional mechanical watches. You could bet your life on Rolex accuracy. Today, every Rolex is a certified chronometer.

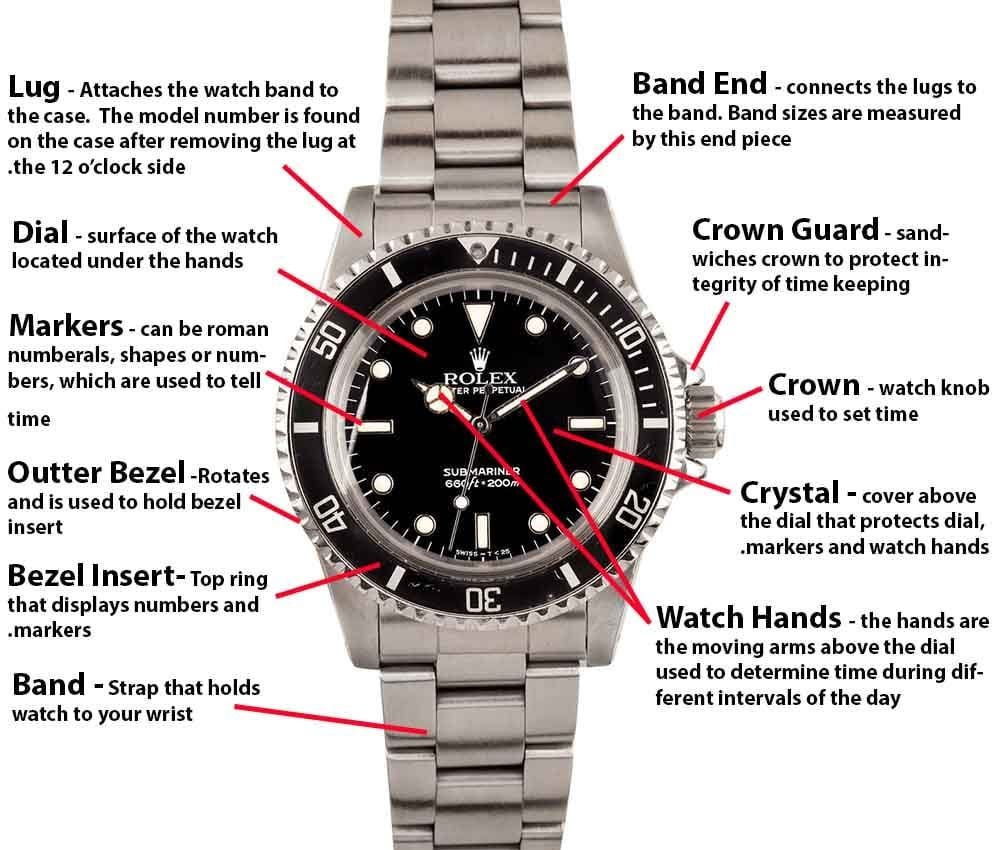

Durable. By 1920, Wilsdorf had moved Rolex to Geneva to be closer to his suppliers and avoid the 33% tariffs that Britain imposed on Swiss watches. World War I had made wristwatches popular since pocket watches were awkward in combat. Now Wilsdorf attacked his second problem: making a waterproof watch. In 1926, he launched his “Oyster” case, which featured a fluted bezel and a screw-down crown.2 In a hint of his marketing genius, Wilsdorf persuaded Mercedes Gleitze, a London typist who had successfully swum the English Channel, to repeat her swim with an Oyster case Rolex around her neck. Gleitze did not complete the swim, but Wilsdorf bought an ad that put her on the cover of the Daily Mail anyway. She became the first Rolex brand ambassador.

Perpetual. Next, Wilsdorf set about to make his watches self-powering. A self-powering movement was essential for Oyster watches because customers often forgot to screw down the crown, which left the watch vulnerable to dust and water. A watch that never needed winding faced no such risk.

Rolex was not the first to make an automatic watch, nor the first to make a waterproof case. Just as Apple is seldom the first to launch a product, Rolex improved on prior innovations. Rolex engineers created an automatic winding mechanism that used a weighted rotor that turns full circles with the motion of your arm (the rotor is the bit of metal that swings around if you have an automatic watch with an exhibition case back). The Rolex invention became the industry's “set it and forget it” standard.3

Today, every Rolex, save for a few dress watches, is labeled Oyster, Perpetual, and Officially Certified Chronometer in honor of these three achievements. Years later, Apple never required a customer to understand computers or phones. Like “set it and forget it,” Apple “just worked.”

Product Development and Manufacturing

Like Apple decades later, Rolex sought to control the quality and distribution of its products through steady, incremental improvement, vertically integrated manufacturing, and an obsessively secretive culture.

Unlike its Swiss competitor Omega, which launches multiple variations of its watches yearly, Rolex watches evolve slowly. Like Apple, however, when Rolex launches a new product, it does so with fanfare and celebrity.

Like Apple, The Crown has always been vertically integrated. Rolex trains their own people and forges their own steel and gold. They manufacture hundreds of parts for each watch, down to the tiniest screws and gears. They design and make their bracelets – which are also technological marvels. Production is highly automated. There are thousands of people involved, but it is not high-horology, old-school craft production like you find at Audemars Piguet, Patek Phillipe, or FP Journe. Its manufacturing processes are obsessive, with dust-free clean rooms, and extensive automation. It is also secretive. Rolex has allowed very few journalists access to its four factories.

Marketing

Rolex marketing starts with product positioning. Throughout the twentieth century, Rolex expanded its engineering capability and introduced innovative new models. In 1945, the Datejust became the first wrist chronometer to feature a date window. In 1956, the Day-Date was the first wristwatch to show both the day and date on the dial. These were everyday watches worn without fuss or attention, and they are now two of the most imitated watches on Earth.

Tool watches. In the 1950s and 1960s, Rolex launched a new type of Rolex: tool watches devoted to specific occupations or activities. These “professional” watch categories came to define watches everywhere. It began with the Submariner – arguably the most important watch in history.

The Sub is the watch many people see when they imagine a Rolex. It was an early dive watch, and many professional divers used it. But that was only part of the point. Submariners are tough and signal affinity with adventurers. They are vaguely glamorous without being ostentatious. Soon, Rolex created several “professional” watches for daily wear. The Submariner for divers, the GMT-Master for pilots and travelers, the Cosmograph Daytona for race car drivers, two Explorers for climbers and adventurers, a Yacht-Master for sailors, and the Milgauss for tech workers exposed to magnetism.4

Lifestyle, not luxury. Rolex marketed tool watches as lifestyle products, not luxury goods. Dealers sold them as attractive, functional, and practical solutions. Rolex pioneered the use of extreme adventure feats and famous brand ambassadors to promote these watches. It was among the first to sponsor bespoke and individualistic sporting events like motorsports, yachting, tennis, and golf.

The shift to luxury branding. During the 1970s, technology disruption forced Rolex to move upmarket. Facing a deluge of accurate, low-cost quartz watches from Japan, Rolex CEO André Heiniger introduced Rolex “Oysterquartz” watches, which today are rare and slightly odd. When that did not work, Heiniger repositioned Rolex as a luxury goods company.

This was a massive change. Luxury brands sell dreams and exclusivity, not usefulness. They emphasize rarity through limited editions, waitlists, or exclusive access to products or events. Scarcity fuels desire and enhances perceived value. Luxury makers often price their wares as “Veblen goods,” with high price points that increase demand by signaling quality, craftsmanship, and status. Luxury marketing tries to create emotional connections with a brand through narratives about heritage, craftsmanship, and prestige. These stories often evoke aspirations and dreams rather than utility. Above all, luxury products are sold through carefully controlled retail stores to maintain exclusivity.

In short, faced with technological innovation and new competitors, Rolex turned tool watches into fool watches. Apple understands precisely how this works.

Iconography. Both Rolex and Apple emphasize the iconic status of their products and brands. They are among the world's most recognized and respected brands. Rolex is synonymous with rugged, prestigious tool watches, while Apple symbolizes innovation, premium design, and user-friendly technology. Customers are loyal to both companies and see their products as status symbols.

Control supply and distribution. Rolex tightly controls production and distribution, using scarcity to maintain exclusivity and demand. Authorized Dealers put customers on waiting lists and insist that you “check in” frequently. (I have never had a call from a Rolex AD, despite regular “check-ins” and four years of waiting.) Apple similarly controls its supply chain, ensuring a balance between availability and desirability, especially with limited initial product releases. Neither company floods the market with products, ensuring their items retain value and exclusivity.

Premium pricing and high margins. Both brands operate a high-margin business model. Rolex watches cost thousands of dollars, driven by quality, brand prestige, and controlled supply. Apple’s devices are among the most expensive in their categories, yet customers justify the price due to brand trust, ecosystem integration, and perceived value.

Invest in engineering innovation and vertical integration. To differentiate its watches, Rolex develops its own movements and materials, such as 904L stainless steel or Cerachrom ceramic bezels. Apple designs its own chips (M-series, A-series) and software (iOS/macOS) and owns its stores. Both companies prioritize proprietary technology to maintain quality and differentiation.

Design evolution, not revolution. Over decades, Rolex refined its core models (Submariner, Daytona, Datejust, GMT Master, Explorer), making subtle improvements rather than drastic changes. Apple does the same with its iPhones, iPads, and MacBooks, keeping a familiar aesthetic while gradually improving technology and features. Both brands understand that radical redesigns can alienate their loyal customer base.

Strong secondary market Rolex watches hold or even appreciate in value, with a thriving resale market. Apple products also have substantial resale value, with iPhones and Macs commanding high prices in the used market. This longevity reinforces the perception that both brands offer durable, long-term investments.

Focus. Rolex doesn’t diversify into other luxury goods. No sunglasses or bomber jackets; it sticks to mechanical watchmaking. Apple resists unnecessary feature bloat and prioritizes refined, deliberate design choices over gimmicks. Both brands have a “we set the trend, not follow it” mentality.

Secrecy and control. Rolex rarely gives interviews, doesn’t discuss production numbers, and carefully curates brand messaging. Apple is famous for its secrecy before product launches and meticulously orchestrated marketing campaigns. Both brands let their products and brand mystique speak for themselves rather than relying on aggressive, transparent marketing.

Build a cult. Rolex fans and collectors are highly dedicated, often waiting years for specific models. Apple users are deeply embedded in the Apple ecosystem, making it hard for them to switch to competitors. Both brands generate emotional attachment, turning customers into lifelong buyers.

Financial independence. Rolex is a nonprofit owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation. It faces no shareholder pressure – and this can be a weakness as well as a strength. Rolex donates about $330 million annually to arts, environmental, and educational causes. While public, Apple has immense financial reserves and strategic control over its direction and contributes substantial sums to nonprofits supported by employees, racial justice, and education. Both companies are financially secure, with no need to chase short-term profits at the expense of long-term brand value.

Results

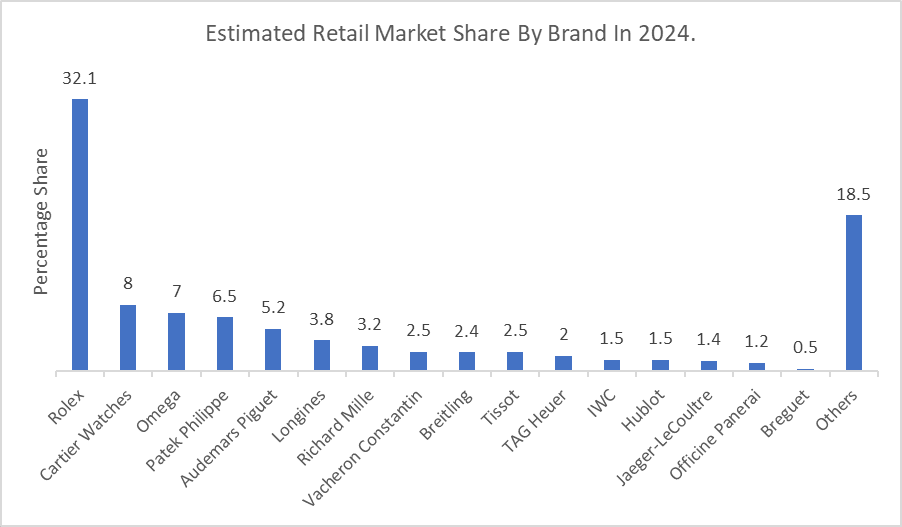

For Rolex, the shift to luxury goods succeeded beyond its wildest dreams. Today, the Swiss represent about 37% of global watch industry revenue despite selling only one percent of the watches. (Apple ships more watches each year than the entire Swiss watch industry.)5 Rolex sells fewer than ten percent of all Swiss watches but books nearly a third of all Swiss watch revenue. Nobody else comes close.

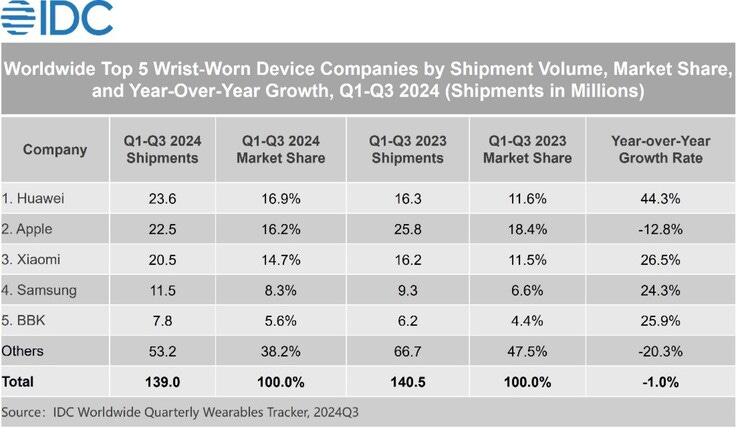

For comparison, Apple sells about 16% of all smartwatches and is seriously challenged by Huawei, Xiaomi, and Samsung in the smartwatch market.

Walled gardens. For companies, as with individuals, nothing kills you faster than your strengths. Apple delivers a lot of value by tightly controlling apps and restricting users' ability to customize their devices. When you click on an address, you get Apple Maps, even if you prefer Google. Your iMessages do not always work well with standard SMS systems. You can only change default apps in limited ways, if at all. Compared with Android, iPhone users forfeit a lot of control over their phones.

A high-control business model mixed with a nonprofit business culture produces all sorts of distortions at Rolex, alongside the obvious strengths. Instead of raising prices, Rolex allocates scarce watches to dealers, who reserve them for customers willing to spend lavishly on jewelry or other watches. They sell used watches at prices 50% higher than new ones. And they spend tens of millions of dollars on marketing and brand ambassadors, creating demand they cannot fulfill. Watch enthusiasts hate this with the passion of a thousand suns. If he were to return to celebrate his birthday today, I have a tough time imagining that Hans Wilsdorf would be pleased with how Rolex treats its customers.

Musical Coda

From my favorite watches to a beautiful synopsis of one of my favorite movies.

Wilsdorf also wanted a name that fit neatly on a watch dial. Jobs wanted a name that would appear before his former employer, Atari, in the phone book.

Rolex no longer screws their bezels into the mid-case, but Rolex fluted bezels live on in several of its most iconic designs.

There are many books on Rolex, and the excellent Acquired podcast recently spent five hours discussing the company's history. I am sure that some of the insights recorded here came from this podcast.

The names reflected Rolex’s continued genius for product names. However, like Apple with Lisa or MobileMe, Rolex has had its share of naming flops. Cellini never worked, and Cerachrom, Parachrom, and Rolesor don’t roll easily off the tongue.

Today, the world produces about 1.2 billion watches, which generate about $77 billion in revenue annually. Last year, Swiss watchmakers produced about 13.3 million of these 1.2 billion units, generating about $28.5 million in revenue.