Do the American left and right agree on trade policy?

To a surprising degree, yes. But should they?

Donald Trump’s preposterous April 2 tariffs and the potentially worse tariffs on China that he announced a week later are a train wreck. Two of Trump’s longstanding beliefs drove these decisions. He decided long ago that Americans always get ripped off whenever we buy anything overseas. And he strongly prefers policies that increase his personal authority, especially if they are chaotic. Nothing here is an attempt to justify or sanewash this imbecility.

But progressive Democrats have not criticized Trump’s shambolic approach with much vigor because many of them quietly support tariffs. To understand this more clearly, imagine a politician who articulated a five-point position on trade:

Free trade is not truly free. Trade gets distorted by foreign subsidies, tariffs, non-tariff barriers, and currency manipulation. China, South Korea, Germany, and Japan have developed as export-driven economies by using protectionist measures that persisted long after they achieved prosperity.

Manufacturing is a strategic asset that drives innovation and productivity. It supports middle-class jobs and career paths for non-college workers while contributing to national security and economic resilience. Relinquishing our ability to produce semiconductors, vaccines, PPE, or warships at scale was unnecessary and, in some cases, dangerous.

Chronic trade deficits with China are dysfunctional. Allowing China to hollow out the US industrial base has reinforced our national preference for low-cost consumer goods over our productive capacity. This situation has created security risks. The rapid trade shift to China created the “China Shock,” which displaced 2.8 million manufacturing workers between 2001 and 2018 and an additional million workers whose jobs depended on them.

Market prices rarely capture social costs. The low prices of Chinese-made consumer goods do not reflect the cost of collapsing domestic industries, local communities, and skilled labor markets. These costs are borne by individuals and communities, not by consumers.

Tariffs are a tool for building industrial capacity. They are not the only tool, nor the most valuable one. They are part of a toolkit that includes scientific research, research and development subsidies, worker training, infrastructure investment, and the coordination of public-private industrial development.

This is mainstream thinking in 2025 for both liberals and many conservatives. Bernie Sanders, AOC, Elizabeth Warren, and Joe Biden would find little to object to. Likewise, nothing in these principles contradicts the writings of New Right conservatives like Oren Cass, Andrew Sullivan, Michael Lind, Marco Rubio, or JD Vance.1 What is going on?

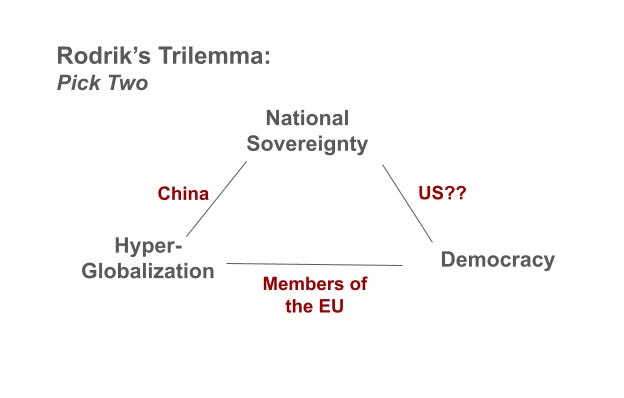

Rodrik’s Trilemma

“Rodrik’s Trilemma” is a good starting point for any discussion of trade policy. In 2011, Harvard economist Dani Rodrik articulated a famous paradox. Every country can have only two of the following three: democracy, national sovereignty, or hyper-globalization. Fundamental incompatibilities mean that no country can have all three simultaneously – although the US has arguably tried.

Rodrik argues that nations typically want all three: fully open borders for goods, services, and capital with minimal regulatory differences between countries (hyper-globalization); national sovereignty or self-determination; and democratic politics (meaning governments that are accountable to citizens, responsive to voters, and led by effective democratic institutions).

Rodrik shows that any country that pursues hyper-globalization and national sovereignty will inevitably weaken its democracy because economic policy will be shaped by international market pressures and global institutions like the EU or WTO, leaving voters with fewer meaningful choices. China, which cares little for democracy, can prioritize national sovereignty and hyper-globalization. Presume that the US wishes to prioritize democracy and national sovereignty. In that case, it will discover that it must limit deep globalization because democratically chosen domestic policies (such as labor, environmental, or trade rules) typically conflict with unrestricted international markets.2

Rodrik concludes that a sustainable world order requires sacrificing some degree of hyper-globalization to preserve democratic accountability and national sovereignty. He suggests countries adopt a “thin globalization” that allows trade and cooperation but still gives democratic nations space to tailor domestic policy to their voters’ wishes.

This trilemma has led both parties to use anti-neoliberal populism to proclaim how little confidence they have in markets to meet the needs of American workers. The parties take different approaches: Democrats champion regulations on Wall Street, investments in semiconductors and critical defense technologies, more equitable trade practices (including continuing most of Trump’s tariffs), and stronger labor rights. Because Trump viscerally dislikes both trade and immigration, Republicans have come to prefer high and unpredictable tariffs, deportations, and border controls.

Effective trade policy requires more than a critique of neoliberalism

Despite surprisingly specific areas of agreement, however, hyper-partisanship makes it hard for either party to confront fully the policy risks that come with their views.

Shared national goals. All Americans want global trade to serve our national interests. But which ones? For which goals should we sacrifice economic growth? Beyond national defense (and perhaps helping to grow the earnings of non-college voters), we have very few shared and achievable industrial and social priorities that we can advance by restricting trade.

Reshoring manufacturing. Both Democrats and Republicans like the idea of re-shoring manufacturing. Bringing production back to the US is possible and sometimes desirable. The United States has rebuilt our solar and battery manufacturing capacity from zero to self-sufficiency (although we import some critical inputs). A recent report from the CHIPS Program Office summarizes our remarkable progress in bringing back semiconductor manufacturing:

“..for the first time, all five of the world’s leading-edge logic and dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) manufacturers (Intel, Micron, Samsung, SK hynix, and TSMC) are building and expanding in the United States. By contrast, no other economy in the world has more than two of these companies manufacturing on its shores…

“The United States is projected to produce at least 20 percent of the world’s leading-edge logic chips by 2030 (up from zero percent in 2022) and ~10% of its leading-edge DRAM chips by 2035 (also up from zero percent)—both technologies that are essential to the future of artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance compute, and advanced military systems. TSMC’s Arizona facility has already begun volume production of leading-edge chips, marking the first time in roughly a decade that a new fab is making these technologies domestically.”

Will it grow bottom quartile earnings? On the other hand, manufacturing employment is declining worldwide – even in China.3 Unfortunately, policy professionals pining to restore mass production have rarely worked on an assembly line. They tend to see all manufacturing work as glorious. My years in factory work taught me the benefits of service sector jobs, which are safer and now pay more.4

Protectionism has earned its poor reputation. Each of the five trade principles mentioned above can protect complacent incumbents, delay technological innovation, incur retaliation, weaken global alliances, and obstruct healthy competition.

Congress labels industries as “strategic” for political convenience, to respond to lobbying pressure, or due to economic nationalism rather than genuine strategic value. During the 1990s, I helped the Labor Department argue that flat-panel TV manufacturing was critical for future technological dominance and required subsidies and protection from Japanese and Korean competition.5 It turns out that competitive markets do a good job with commodities like consumer electronics.

Since the 1930s, America has protected sugar to ensure “food security”. As a result, we pay twice the world market price.6 Starting in the 1950s, we subsidized wool and mohair on the theory that it went into military uniforms. We subsidize peanuts in the name of “agricultural independence”. Through the 1980s-90s, we subsidized shoe and apparel making as vital to “maintaining industrial capability” even though these industries posed no real strategic threat when they moved offshore.

Even industries like shipbuilding, with obvious national security implications, do not benefit from the wrong kind of protection. We shielded our shipbuilders from international competition – and they collapsed. China poses a potential naval threat with a significantly higher shipbuilding capacity than the US, which constructs fewer than one percent of global commercial ships.

American ships cost four to five times more to build than their foreign counterparts. Because our remaining shipyards face minimal competition, they rarely innovate, charge inflated prices, and continue to decline.7 Instead of creating a globally competitive shipbuilding sector, protectionism has fostered dependency and decay. This is not an argument against industrial policy. After all, countries like Korea and Japan support shipbuilding through investment, training, and R&D rather than by closing their markets.

Confusing ends and means. For Donald Trump, tariffs are the point. He favors them for emotional reasons that do not withstand freshman scrutiny. Tariffs are one of several tools to correct distortions, support domestic strategy, and deal with foreign economies that are state-driven, not market-driven. Like a five-pound sledge, however, tariffs are blunt instruments and are only occasionally the right tool for the job. Using tariffs as a retaliatory trade measure is often politically popular but rarely compels trading partners to reverse their policies.

Humility

If the history and politics of trade policy teach anything, it should teach humility – a lesson the current administration will never learn. When asset markets respond to your policies by shedding trillions of dollars, when stocks in manufacturers like Boeing – the supposed beneficiaries of your plans – plummet, when nearly every leading economist argues that your policies are disastrous, a leader with an ounce of epistemic humility might pause for at least a moment. The markets are not the economy, but when global financial markets powered by billions of dollars and countless investors scream warnings, it’s a good time to reconsider your confidence level. Permanent tariffs do not create industrial titans. They create Argentinas.

If your goal is shrinking the trade deficit—though it’s unclear why you think that’s necessary—the proven path isn’t tariffs; it’s boosting national savings, investing in a stronger workforce, investing in R&D, cutting deficits, and encouraging smarter investment habits. To dismiss the market, ignore the experts, and push the button on tariffs when the economic fate of billions of people hangs in the balance is a sign not of confidence but of unbounded egotism.

Coda

Michael Lind and Andrew Sullivan are conservatives who dislike Trump and may not be registered Republicans.

My diagram suggests that China values globalization and sovereignty at the expense of democracy, members of the EU value globalization and democracy at the expense of national sovereignty, and the US, having tried to have all three, will likely value sovereignty and democracy at the expense of hyper-globalization. This overlay is mine, not Rodrik’s.

The last time America went all-in to preserve family-supporting jobs threatened by fundamental economic changes, we passed the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariffs to try and save family farms. These tariffs not only worsened the Depression, but Congress recognized that Smoot-Hawley was such a legislative failure that it transferred tariff authority to the executive branch. Derek Thompson just released a great podcast episode detailing this story here.

Historically, manufacturing jobs paid more, but as of March, the average manufacturing sector job paid $35.16/hour compared to the average private service-providing job, which paid $35.81. Since public sector jobs average $63.46/hour and consist entirely of services, the average service sector job plainly pays more than the average manufacturing job. The standard caveats about using averages apply here in force.

I opposed these measures at the time but proudly served in an administration that took a different view.

Of course, this reduces the demand for sugar, which was not the goal but is probably fine.

Brian Potter has conducted an excellent deep dive into the collapse of US shipbuilding.

I will send you a copy of my Quarterly article called The Enemy is the Mindset. It is strangely relevant after 30 years.